Connections

with the Phonograph

By

Willa Cather ©1922, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

By Doug Boilesen, 2022

Each book selected by Friends of

the Phonograph in Phonographia's Library

of PhonoLiterature has at least one phonograph in its story.

One of Ours by Willa Cather has

several phonographs but many more phonograph connections (primarily

songs which became popular phonograph records during World War I)

with its discography

(playlist) larger than any other book in the PhonoLiterature Library.

These connections are also historically

noteworthy because World War I music was an important part of the

"messaging" which supported the Allies at home and in the

trenches. As Neil Harris and Teri Edelstein wrote in En Guerre:

French Illustrators and World War I, the production of unending

messages "with a consumerist orientation" was for the most

part "to bolster morale, arouse indignation, ridicule the enemy,

glorify heroic traditions, add some needed humor, and satisfy the

need for diversion during the long agonies of war." (1)

Organized by subjects, each section

of this page starts with text from One of Ours.

Strings

in the following subjects include endpoints which are phonographs,

phonograph records, sheet music and other phonograph related connections.

Connections

with the Phonograph

Subjects include the following:

"Bidding

the eagles of the West fly on . . .", Mechanical

Devices, the Phonograph,

Dislike of Phonograph Music,

Dull without the Phonograph

on Winter Evenings, Phonograph

Monologues, David

Hochstein, Neutrality,

Edith Cavell, the Lusitania,

the United States's Entry into

the War, Submarine Warfare,

His Master's Voice, Battle

of the Marne, Claude Prepares

for France, Camp Dix,

"Good-bye Broadway, Hello

France," "Statue

of Liberty," "Over

There," Claude's

Ship Arrives in France, General

Pershing, Trench Warfare,

"Home, Sweet Home,"

Aeroplanes and Victor Morse,

Support for the Troops,

the Bugle,

A Mother's loss, Armistice,

Good-Bye France, "Everybody's

Happy Now," Summary

and Discography.

LISTENING to RECORDS and the BACK

Button

All records on this page can be played

(see Instructions for listening to

records), however, this page is not optimized for small screens. If

you are using an iPad see iPad Back

Button for related information.

"Bidding

the eagles of the West fly on . . ."

"One of Ours

is the intimate story of a young man's life. Claude

Wheeler's stormy youth, his enigmatic marriage, and the final

adventure which releases the baffled energy of the boy's nature..."

Excerpt from cover of the 1922

novel written by Alfred E. Knopf, publisher of One of Ours.

Mechanical Devices

The first reference to the phonograph

in One of Ours is not specific but sets the context of Ralph's

acquisitions of mechanical contraptions and his upcoming purchase

of "another music machine." There is an on-going debate

between Ralph and his mother, Mrs. Wheeler, who admits that she is

"old-fashioned" and struggles to use any of the devices

Ralph has purchased for her home, seeing them also as a waste of money.

It starts with the cream separator.

"Now, Mother," said Ralph good-humouredly,

as he emptied the syrup pitcher over his cakes, "you're prejudiced.

Nobody ever thinks of skimming milk now-a-days. Every up-to-date

farmer uses a separator."

Mrs. Wheeler's pale eyes twinkled.

"Mahailey and I will never be quite up-to-date, Ralph. We're old-fashioned,

and I don't know but you'd better let us be. I could see the advantage

of a separator if we milked half-a-dozen cows. It's a very ingenious

machine. But it's a great deal more work to scald it and fit it

together than it was to take care of the milk in the old way."

"It won't be when you get used to

it," Ralph assured her. He was the chief mechanic of the Wheeler

farm, and when the farm implements and the automobiles did not give

him enough to do, he went to town and bought machines for the house.

As soon as Mahailey got used to a washing-machine or a churn, Ralph,

to keep up with the bristling march of events, brought home a still

newer one. The mechanical dish-washer she had never been able to

use, and patent flat-irons and oil-stoves drove her wild. (pp. 32-33)

More examples follow of "mechanical

toys" and "mysterious objects" purchased by Ralph.

The cellar was cemented, cool and

dry, with deep closets for canned fruit and flour and groceries,

bins for coal and cobs, and a dark-room full of photographer's apparatus.

Claude took his place at the carpenter's bench under one of the

square windows. Mysterious objects stood about him in the grey twilight;

electric batteries, old bicycles and typewriters, a machine for

making cement fence-posts, a vulcanizer, a stereopticon with a broken

lens. The mechanical toys Ralph could not operate successfully,

as well as those he had got tired of, were stored away here. If

they were left in the barn, Mr. Wheeler saw them too often, and

sometimes, when they happened to be in his way, he made sarcastic

comments. Claude had begged his mother to let him pile this lumber

into a wagon and dump it into some washout hole along the creek;

but Mrs. Wheeler said he must not think of such a thing, as it would

hurt Ralph's feelings very much. Nearly every time Claude went into

the cellar, he made a desperate resolve to clear the place out some

day, reflecting bitterly that the money this wreckage cost would

have put a boy through college decently. (p. 35)

The language of "mechanical"

is also seen multiple times in relation to mechanical actions and

state-of-minds. See One of Ours Endnote "Mechanical"

for examples.

The Phonograph

"The latest make, put out under

the name of a great American inventor."

The phonograph is first identified in

One of Ours with Ralph purchasing another music machine, "the

latest make, put out under the name of a great American inventor."

The next few weeks were busy ones

on the farm. Before the wheat harvest was over, Nat Wheeler packed

his leather trunk, put on his "store clothes," and set off to take

Tom Wested back to Maine. During his absence Ralph began to outfit

for life in Yucca county. Ralph liked being a great man with the

Frankfort merchants, and he had never before had such an opportunity

as this. He bought a new shot gun, saddles, bridles, boots, long

and short storm coats, a set of furniture for his own room, a fireless

cooker, another music machine, and had them shipped to Colorado.

His mother, who did not like phonograph music, and detested phonograph

monologues, begged him to take the machine at home, but he assured

her that she would be dull without it on winter evenings. He wanted

one of the latest make, put out under the name of a great American

inventor. (p. 103)

The latest phonograph made "under

the name of a great American inventor" was, of course, a Thomas

A. Edison Phonograph. The Edison signature was a feature of Edison's

marketing along with the phrase "Genuine Edison Phonograph."

(1A)

This 1900 Cosmopolitan ad includes

Edison's picture with his signature below it and the Edison phonograph

ad tag line: "None genuine without this Thomas A. Edison Trade

Mark " (signature).

Cosmopolitan magazine,

December 1900

Ralph is beginning to "outfit

for life in Yucca county" when he purchases a new Edison phonograph

so the time period is probably between 1906 and 1908.(1AA)

The Edison Home or

Edison Triumph Phonograph would be good possibilities for the

model of the machine Ralph purchased.

(1B). For more about the

phonograph industry's timeline and cylinder vs. disc machines see

(1C). See

(1D) regarding The Willa Cather

Scholarly Edition's One

of Ours Explanatory Note 103.

As the "great American inventor"

and President of Thomas A. Edison, Inc., Edison's phonograph company

would continue through the teens and into the twenties to be one of

the big three in the U.S. phonograph industry. What Edison did and

said was a common item in the popular press. When Edison published

"Messages" to his

Dealers from 1917-1919 in the trade magazine The Talking Machine

World the "Wizard" was offering his perspectives on

the war, business and the importance of music which are themselves

interesting pieces of war-time popular culture.

Mrs. Wheeler "did

not like phonograph music"

His mother, who did not like phonograph

music, and detested phonograph monologues...(p. 103)

The phonograph had its detractors in

its early years but circa 1907 the fact that Mrs. Wheeler "did

not like phonograph music" was a minority opinion and in contrast

to the many consumers who were interested in the growing catalogs

of phonograph music and recorded entertainment: bands, orchestras,

instrumental, musical groups and performing artists; solos by accordian,

banjo, bagpipe, bells, church chimes, clarinet, cornet, dulcimer,

flute, harp, mandolin, oboe, organ, piccolo, piano, piccolo, trombone,

trumpet, violin, violoncello, whistling, xylophone and zither;

and its monologue records, also known as descriptive, vaudeville,

recitation, sketch and "dialect" records. (1E)

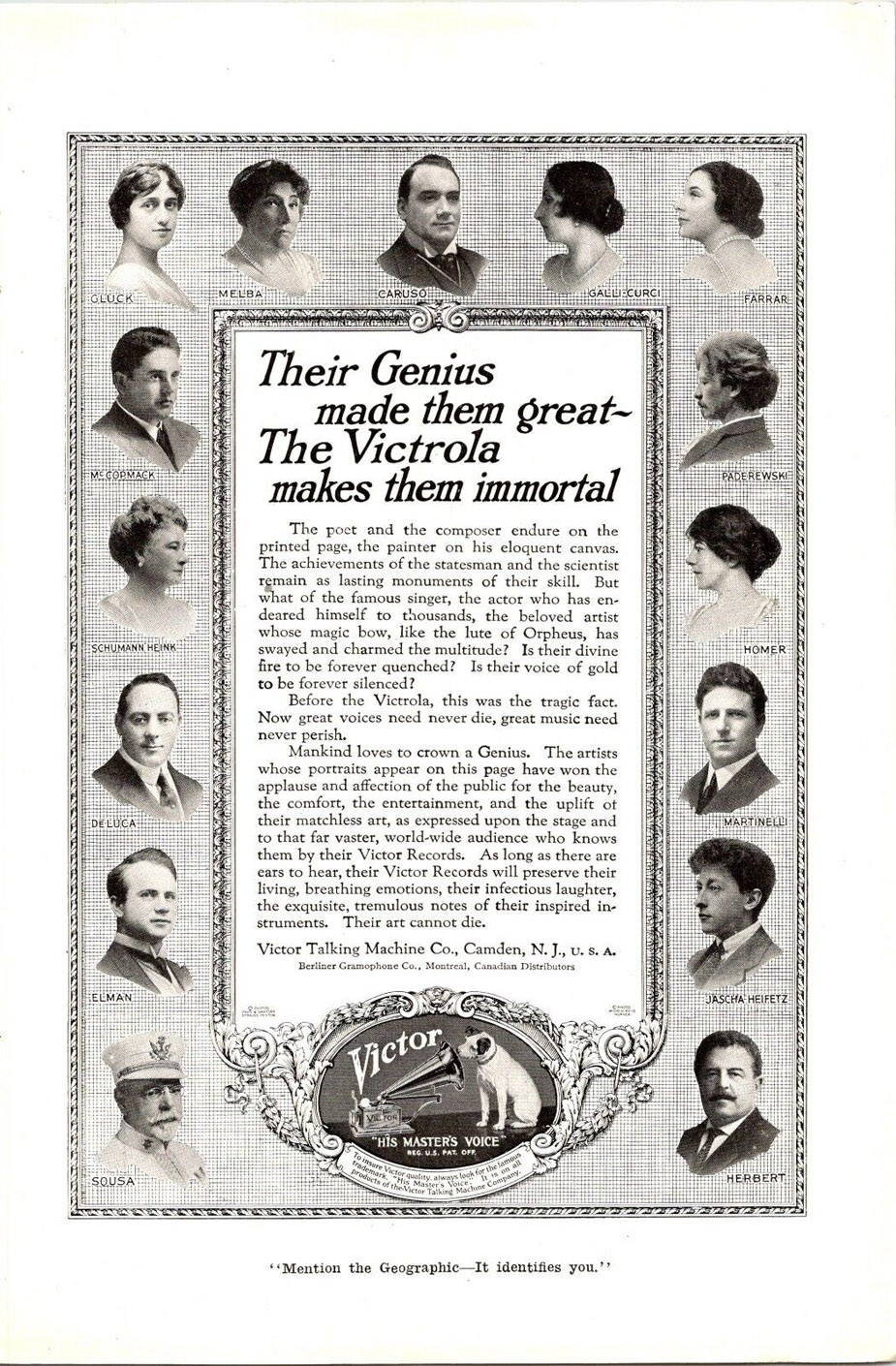

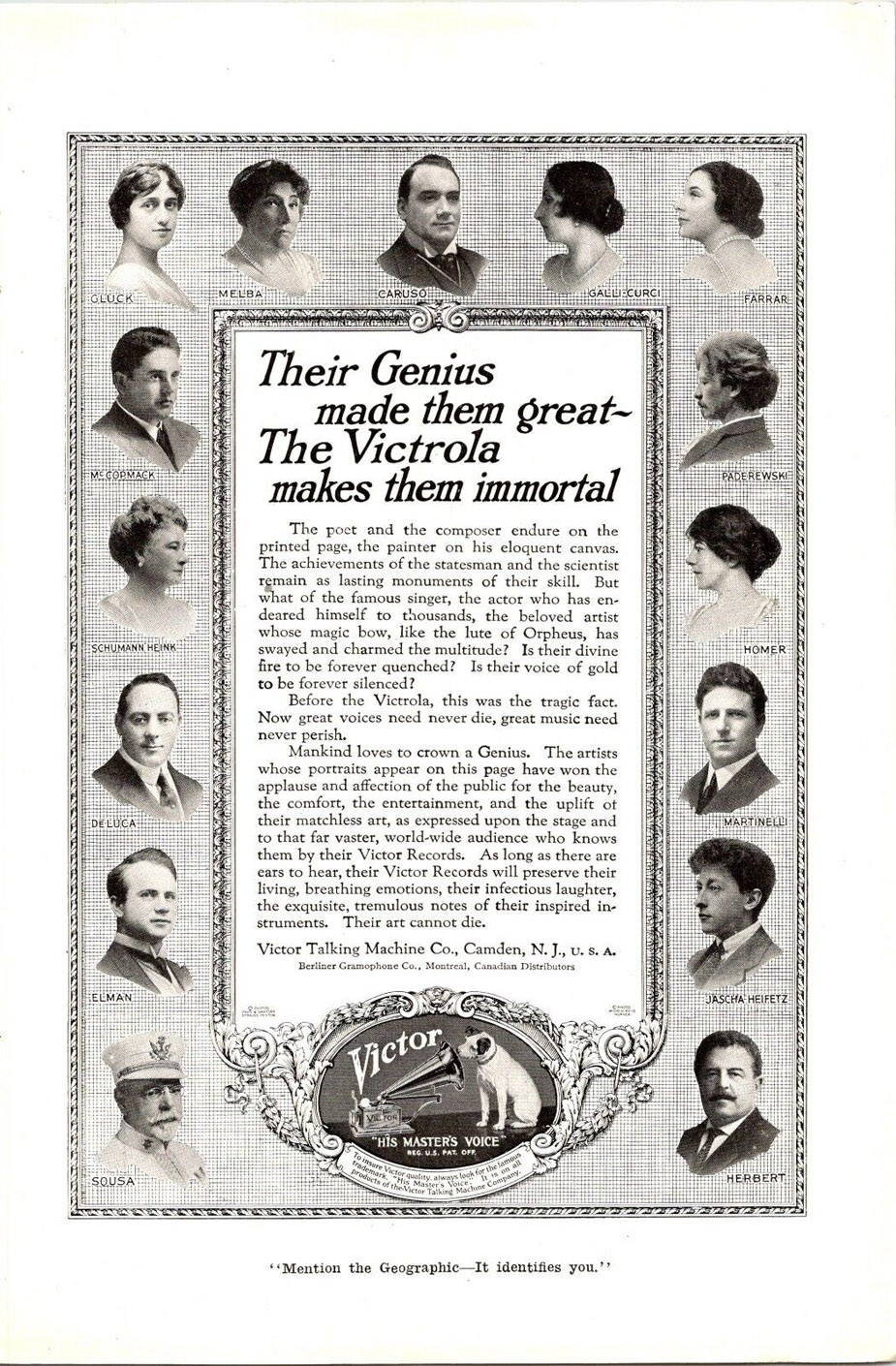

John Philip Sousa, who was well-known

for his band and military march music and who also made records, famously

wrote what he didn't like about player pianos and phonographs in a

1906 magazine article titled "The Menace of Mechanical Music."

Sousa railed against the phonograph and its damage to America's musical

future, warning that "mechanical music was sweeping across the

country" and

was becoming a “substitute for human skill, intelligence and soul.”

"Then

what of the national throat? Will it not weaken?" (1F)

"Will

the infant be put to sleep by machinery" asked Sousa. (1G)

"The Menace of Mechanical

Music" by John

Philip Sousa, Appleton's

Magazine,

September 1906

Mrs. Wheeler "detested

phonograph monologues."

His mother, who did not like phonograph

music, and detested phonograph monologues...(p. 103)

The "monologue" records which

Mrs. Wheeler detested were also known as descriptive, vaudeville,

recitation, sketch and "dialect" records and were first

heard on the nickel-in-the-slot phonographs in the 1890's. Some of

these early monologues and songs contained bawdy and risque content.

In 1891 Russell Hunting began making one of the most famous monologue

record series of its time featuring his Irish character, "Michael

Casey." But Hunting's recording career was interrupted when

he was arrested on June 24,1896 for making and distributing obscene

records. In the case, "widely reported in the press," Hunting

was "sentenced to three months in prison for violating the same

obscenity laws that governed written literature and visual images."

(2). While in jail Hunting also lost

the monopoly over his Casey series but he would continue making records

and nearly twenty-five years later was still making "Casey"

records with his "descriptive" Pathe World War I

record titled "Casey

Home From The Front".

In the first decade of 20th century

Harlan and Stanley had their "Rube

Series" of records (Disclaimer);

Len Spencer had his so called "colorful dialogues" involving

numerous ethnicities; William F. Denny had what Edison advertised

as "his great monologue"

entitled "A

Matrimonial Chat." Billy Golden and Joe Hughes' vaudeville

sketch about the Mexican Expedition (a.k.a. the Pancho Villa Expedition)

titled "Jimmy

Triggers Return from Mexico." Cal Stewart, known as the "Yankee

Story Teller," became famous in his role as Uncle Josh Weathersby

and his Edison record titled Uncle

Josh and the Lightning Rod Agent is an example of his New England

humor.

Columbia, Victor and other talking machine

companies besides Edison made "monologue" records and performers

like all of the above recorded for multiple companies. Edison therefore

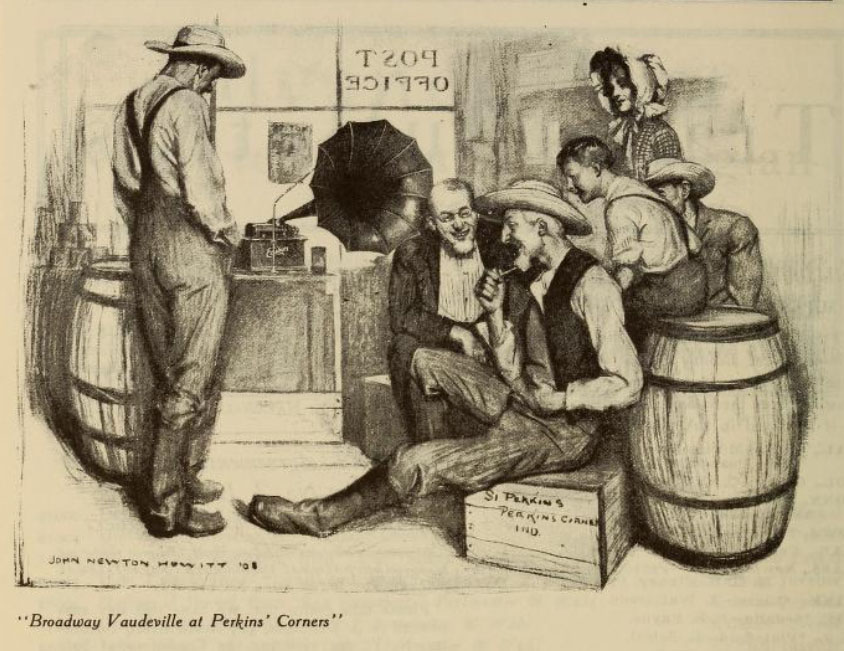

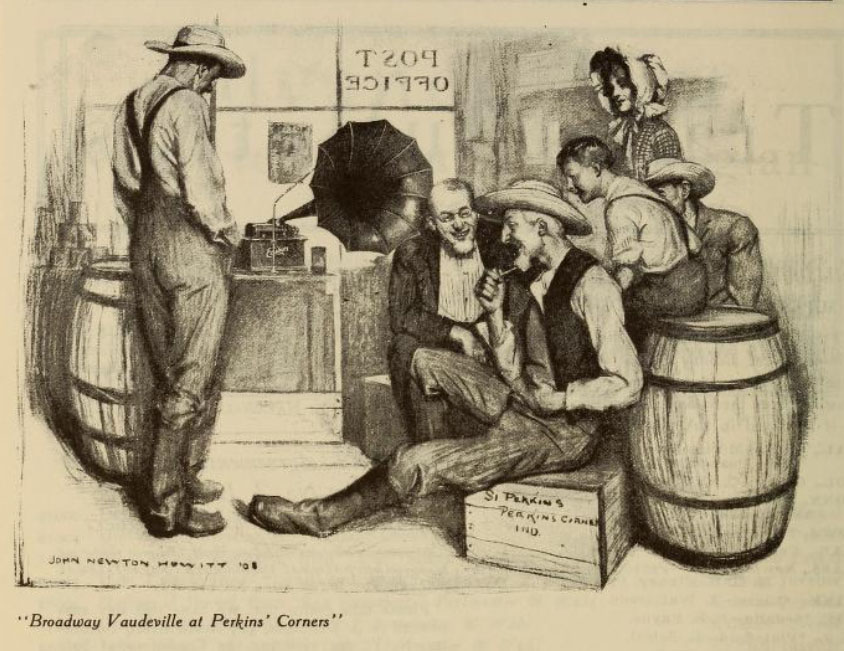

wasn't alone in making monologue records, however, the following 1908

Edison ad for "Broadway Vaudeville" featuring entertainment

by Uncle Josh shows popular culture that is probably a closer fit

for a Nebraska homestead than the opera stages promoted by Victor

and Columbia.

No record, however, was welcomed in

Mrs. Wheeler's Nebraska home, and especially any phonograph monologue.

The Edison Phonograph Monthly

showing what Edison was using for their August 1908 national advertisements.

In contrast to the phonograph monologues

and recitations, a variety of music and opera was offered to its listeners

presenting "The whole show" and "The

Stage of the World." "A single evening with the Graphophone

offers thousands of dollars in professional services." Its scientific

improvements, said a 1906 Columbia ad, "have resulted in reproducing

the exact human tone quality and volume of the original."

"Ring Up the Graphophone

Curtain in Your Home, and the Whole World of Entertainment Appears!"

1906

"Verdi's Masterpiece,

"Il Trovatore", complete, from the opening chorus to the finale

of the last act...of the La Scala Theatre, Milan, Italy." Munsey's,

Victor Talking Machine Co., 1906

"dull without

it on winter evenings."

Ralph is buying another phonograph for

his new home and his mother doesn't want him to leave the old one

with her.

His mother...begged him to take

the machine at home, but he assured her that she would be dull without

it on winter evenings. (p. 103)

The phonograph, as it became a consumer

product in the mid-1890's, started to increase its phonograph advertising

and this included repeatedly promoting it as the “finest entertainer

in the world,” "always ready to entertain," and the clear

answer for how to spend your evenings (especially in the long, cold,

dark, shivery evenings"):

Top section of 1899

broadside advertisement.

See Evenings

in Any Season are Never Dull with a Phonograph for advertising

examples of the phonograph as the unmatched entertainer for any evening.

See "Antique Phonograph, Gadgets,

Gizmos & Gimmicks" for a novelty trade card depicting "a

dull evening at home," circa 1908. By holding the card to the

light a Zon-O-Phone magically appears as the "Ideal Home Entertainer

- it drives dull care away." (2A)

"singing snarl

of a phonograph."

The next reference to the phonograph

was less than complimentary regarding listening to the "singing

snarl of a phonograph."

That evening Claude was sitting

on the windmill platform, down by the barn, after a hard day's work

ploughing for winter wheat. He was solacing himself with his pipe.

No matter how much she loved him, or how sorry she felt for him,

his mother could never bring herself to tell him he might smoke

in the house. Lights were shining from the upstairs rooms on the

hill, and through the open windows sounded the singing snarl of

a phonograph. (p. 110)

"before the

days of Victrolas."

The Victrola was introduced by the Victor

Talking Machine Company in 1906. Its popularity would make it a generic

term for early phonographs and talking machines, especially for machines

with their horn enclosed within its cabinet. Edison's "Phonograph"

was also a trade-marked name that in the U.S. would become a generic

term for record players. See Phonographia's PhonoAds

Pre-1900 for more details about the early marketing of the phonograph

as a home entertainment machine prior to the introduction of the Victrola.

Claude decided he would go to the

Yoeders' today, and to the Dawsons' tomorrow. He didn't like to

think there might be hard feeling toward him in a house where he

had had so many good times, and where he had often found a refuge

when things were dull at home. The Yoeder boys had a music-box long

before the days of Victrolas, and a magic lantern, and the old grandmother

made wonderful shadow-pictures on a sheet, and told stories about

them. She used to turn the map of Europe upside down on the kitchen

table and showed the children how, in this position, it looked like

a Jungfrau; and recited a long German rhyme which told how Spain

was the maiden's head, the Pyrenees her lace ruff, Germany her heart

and bosom, England and Italy were two arms, and Russia, though it

looked so big, was only a hoopskirt. This rhyme would probably be

condemned as dangerous propaganda now! (p. 340)

The 1907 Victor-Victrola

the Sixteenth 1907-1921 (Courtesy of WorthPoint) See

End Notes 'Victrolas' for more details.

"music-machines

poured out jazz tunes and strident Sousa marches"

"From every doorway music-machines

poured out jazz tunes and strident Sousa marches. The noise was stupefying."

The sidewalks were crowded with

chairs and little tables, at which marines and soldiers sat drinking

sirops and cognac and coffee. From every doorway music-machines

poured out jazz tunes and strident Sousa marches. The noise was

stupefying. Out in the middle of the street a band of bareheaded

girls, hardy and tough looking, were following a string of awkward

Americans, running into them, elbowing them, asking for treats,

crying, "You dance me Fausse-trot, Sammie?" (p.

437)

"Jazz, Fox-Trot"

("You dance me Fausse-trot,

Sammie?")

Original Jazz, Fox-Trot "

The Kaiser's Got the Blues," by Waldron, F. D., published by

Frank D. Waldron, Tacoma, 1918 (Courtesy Library of Congress)

"noise of the

phonograph"

The violin and recording artist David

Gerhardt (who was largely based on the concert violinist David Hochstein)

kept his concentration despite the talk and noise of the phonograph.

(2AA)

Claude knew that David particularly

detested Captain Owens of the Engineers, and wondered that he could

go on working with such concentration, when snatches of the Captain's

lecture kept breaking through the confusion of casual talk and the

noise of the phonograph. Owens, as he walked up and down, cast furtive

glances at Gerhardt. He had got wind of the fact that there was

something out of the ordinary about him. (p. 488)

David Hochstein and the powers of

the phonograph

The phonograph's powers to capture and

share music anywhere and anytime exemplifies the unique attributes

of the phonograph and its records. The "anywhere" allows

music to be shared no matter where someone is located. The "anytime"

removes restrictions both for when one can listen but also as for

whether or not the performer is even alive. As the Victor ad of 1918

stated "Jenny Lind is

only a memory, but the voice of Melba can never die."

Phonograph records preserved the art

of violinist David Hochstein, the prototype for Lieutenant David Gerhardt,

so that his art could potentially be shared with anyone at anytime.

If Claude's mother could hear Gerhardt's records Claude believed that

"it will sort of bring the whole thing closer to her, don't you

see?"

David Hochstein (Courtesy Rochester

Public Library) and G.P. Cather in Nebraska National Guard, 1916

(Illustration 14, One of Ours, Willa Cather Scholarly Edition,

2006, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln)

The men kept the phonograph going;

as soon as one record buzzed out, somebody put in another. Once,

when a new tune began, Claude saw David look up from his paper with

a curious expression. He listened for a moment with a half-contemptuous

smile, then frowned and began sketching in his map again. Something

about his momentary glance of recognition made Claude wonder whether

he had particular associations with the air,—melancholy, but beautiful,

Claude thought. He got up and went over to change the record himself

this time. He took out the disk, and holding it up to the light,

read the inscription: "Meditation from Thaïs—Violin solo—David Gerhardt."

When they were going back along

the communication trench in the rain, wading single file, Claude

broke the silence abruptly. "That was one of your records they played

tonight, that violin solo, wasn't it?"

"Sounded like it. Now we go to the

right. I always get lost here."

"Are there many of your records?"

"Quite a number. Why do you ask?"

"I'd like to write my mother. She's

fond of good music. She'll get your records, and it will sort of

bring the whole thing closer to her, don't you see?"

"All right, Claude," said David

good-naturedly. "She will find them in the catalogue, with my picture

in uniform alongside. I had a lot made before I went out to

Camp Dix. My own mother gets a little income from them. Here we

are, at home." As he struck a match two black shadows jumped from

the table and disappeared behind the blankets. "Plenty of them around

these wet nights. Get one? Don't squash him in there. Here's the

sack."

Gerhardt held open the mouth of

a gunny sack, and Claude thrust the squirming corner of his blanket

into it and vigorously trampled whatever fell to the bottom. "Where

do you suppose the other is?"

"He'll join us later. I don't mind

the rats half so much as I do Barclay Owens. What a sight he would

be with his clothes off! Turn in; I'll go the rounds." Gerhardt

splashed out along the submerged duckboard. Claude took off his

shoes and cooled his feet in the muddy water. He wished he could

ever get David to talk about his profession, and wondered what he

looked like on a concert platform, playing his violin. (pp. 488-490)

"She will find them in the catalogue,

with my picture in uniform alongside."

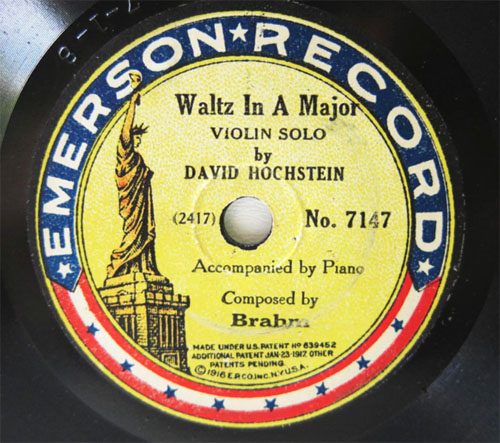

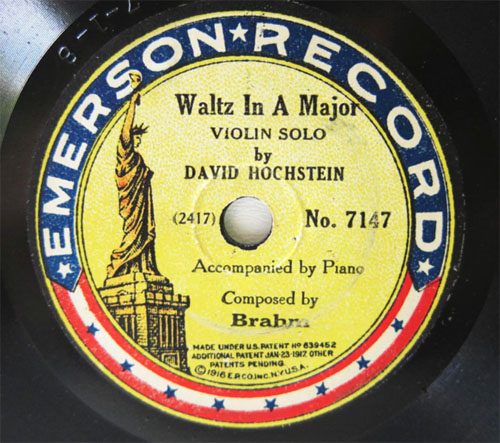

David Hochstein has two selections and

his photograph in the 1917 Emerson Records catalog: Fritz Kreisler's

"Liebesleid" and "Waltz in A Major" by Brahms.

Listen

to David Hochstein play Fritz Kreisler's "Liebesleid" courtesy

of Hochstein.org.

"Waltz in A Major,"

Violin Solo by David Hochstein, 1916

No record catalog has been located with

Hochstein in uniform, however, Albert Spalding, a famous violinist

who recorded for Edison also served in France in the United States

Air Corps and there is one for him. Spalding received much publicity

for his service and there are concert publicity photographs with Spalding

in uniform. See Albert Spalding, Edison

artist and violinist in France who later made a Victor record of Hochstein's

arrangement of Brahms Waltz

in A Major.

1917 Emerson Record

Catalog, p. 10 (Courtesy Internet

Archive)

The Neutrality of the United States

"The United States remained

neutral at the beginning of the war. Americans were divided in support,

although the majority were sympathetic to the Allies. Many contributed

to relief efforts; others volunteered as ambulance drivers or nurses,

or even as pilots and soldiers. Most, however, agreed with President

Woodrow Wilson’s commitment to keeping the U.S. out of the fighting."

(1)

THE TUG OF PEACE - satirical

cartoon of pacifist and industrialist Henry Ford's attempt to initiate

a peace process among the belligerents during of WWI. Punch,

December 15, 1915 (PM-1036)

The Neutrality March by Mike

Bernard, publisher Chas. K. Harris, New York, 1915. (Courtesy

The

Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, The Sheridan Libraries,

Johns Hopkins University) Midi version of The Neutrality March

can be heard on YouTube.

There was no record released for The

Neutrality March but in 1915 Bert Williams sang "I'm Neutral"

since neutrality was President Wilson's official position and a much

discussed topic in the United States.

"I'm Neutral" sung by Bert

Williams Columbia Grafonola Record A1817, 1915 (Courtesy

David Giovannoni Collection i78s.org)

"There ain't no use in talking,

folks are all up in the air...but I'm Neutral, I am and is and shall

remain just neutral..." Bert Williams

"Based on President Woodrow Wilson's

isolation stance in the early years of the first World War, "I'm

Neutral" playfully represents the challenge of remaining neutral.

The protagonist finds himself, as did most of Williams's characters,

in unfortunate circumstances. Faced with acquaintances of different

ethnic backgrounds who are biased about the war in Europe, he tries

not to get involved. In the agitated spirt of the environment, however,

he is attacked. The second verse situates him amid a fighting husband

and wife." (Ann Ommen Van der

Merwe, The Ziegfield Follies: A History in Song)

The lyrics begin with "there ain't

no use in talkin" but "somebody hocked the Kaiser and

I don't know the reason why."

"There ain't no use in talking,

folks are all up in the air, From what I can hear them saying seems

like fightin everywhere, I went down to the bulletin board the other

night, just to see what I could see, and before I knew it there

was several hundred men all surrounding me, somebody hocked the

Kaiser and I don't know the reason why, but a Frenchman took a swing

at me and dug a trench right in my eye A Russian saw my color and

he yelled "kill the Turk!" then the alley's all got in

the range and started in the works... But I'm Neutral, I am and

is and shall remain just Neutral.."

"When the Kaiser is in Hock,"

by John Peach Gilroy, Asplund & Leaf Music Printers, Seattle,

1917 (Courtesy Library of Congress)

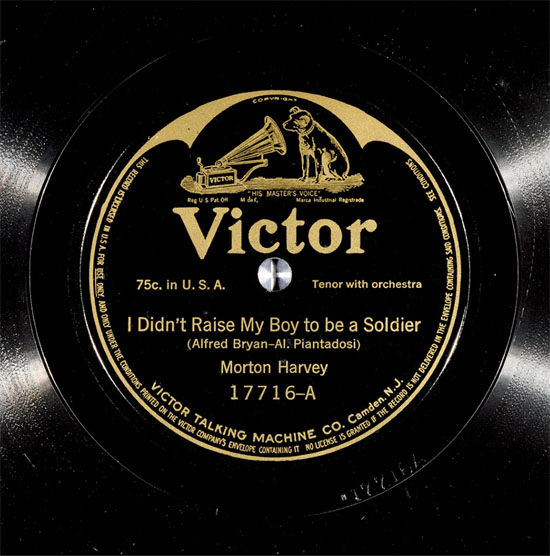

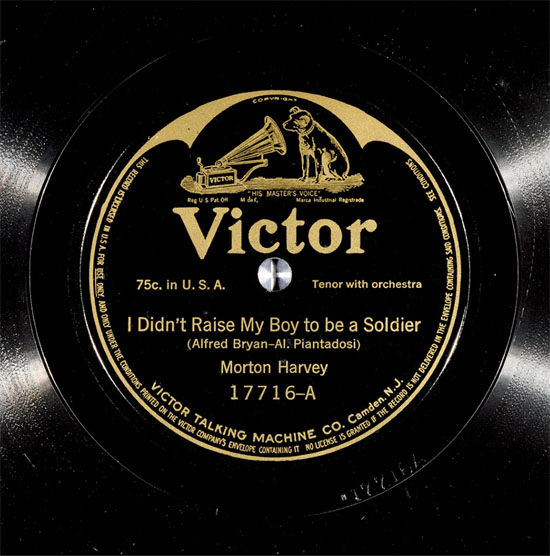

The song "I Didn't Raise My Boy

to be a Soldier" was promoted as a "sensational anti-war

song hit." It would be recorded on several labels in 1915, among

them by Morton

Harvey for Victor Records; the Peerless

Quartette recorded on January 6, 1915 for Columbia Records; Helen

Clark recorded on February 15, 1915 for Edison Records; a Medley

One-Step version by

Jaudas' Society Orchestra recorded on May 11, 1915 for Edison

records. Each can be heard courtesy of David Giovannoni.

Sheet music and record

label courtesy of Giovanonni-Sheram Collection.

Listen

to Morton Harvey, Victor Records 17716-A (Courtesy of i78s.org and

David Giovanonni).

The United States remained neutral

even after Edith Cavell's execution and the sinking of the Lusitania

"On 7 May 1915 a German submarine

torpedoed and sank the British passenger liner Lusitania off the coast

of Ireland. Of 1,257 passengers, 1,198 died, among them 128 Americans.

President Wilson declared the sinking illegal and inhumane and asserted

that it represented a violation of "sacred human rights." The Lusitania

became a focus of both American and German propaganda....Most Americans,

though angered at the incident, called for negotiations with Germany.

In February 1916 Germany officially apologized to the United States

and offered an indemnity." One of Ours, Willa Cather

Scholarly Edition, ibid, Explanatory Note No. 293.

"Don't let me forget to give you

an article about the execution of that English nurse." "Edith Cavell?

I've read about it," he answered listlessly. "It's nothing to be

surprised at. If they could sink the Lusitania, they could shoot

an English nurse, certainly." (p. 286)

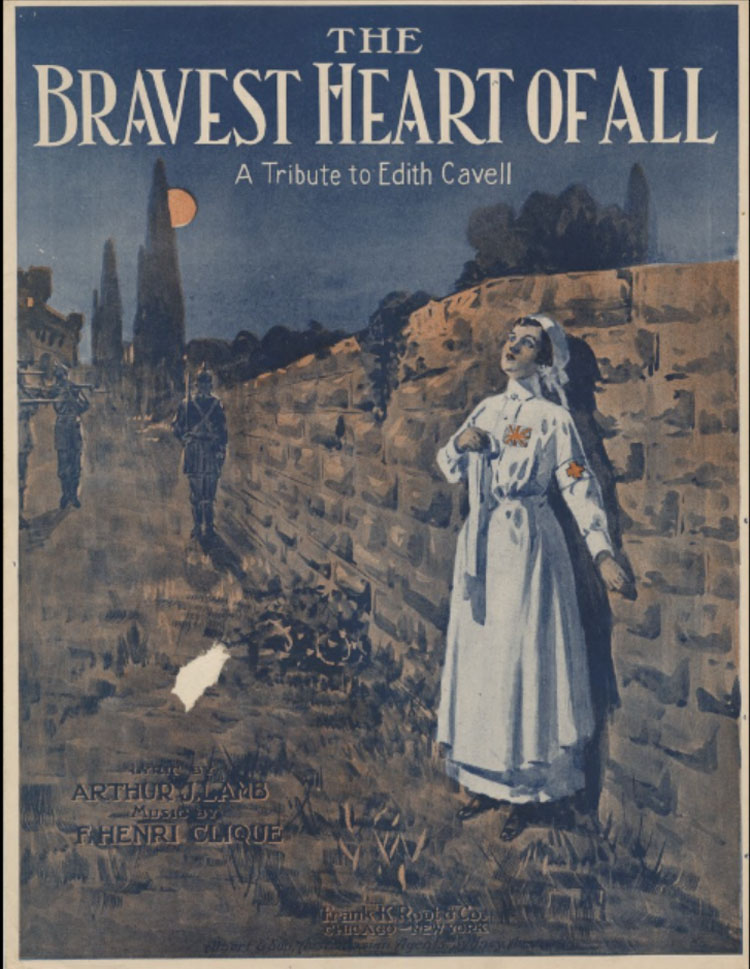

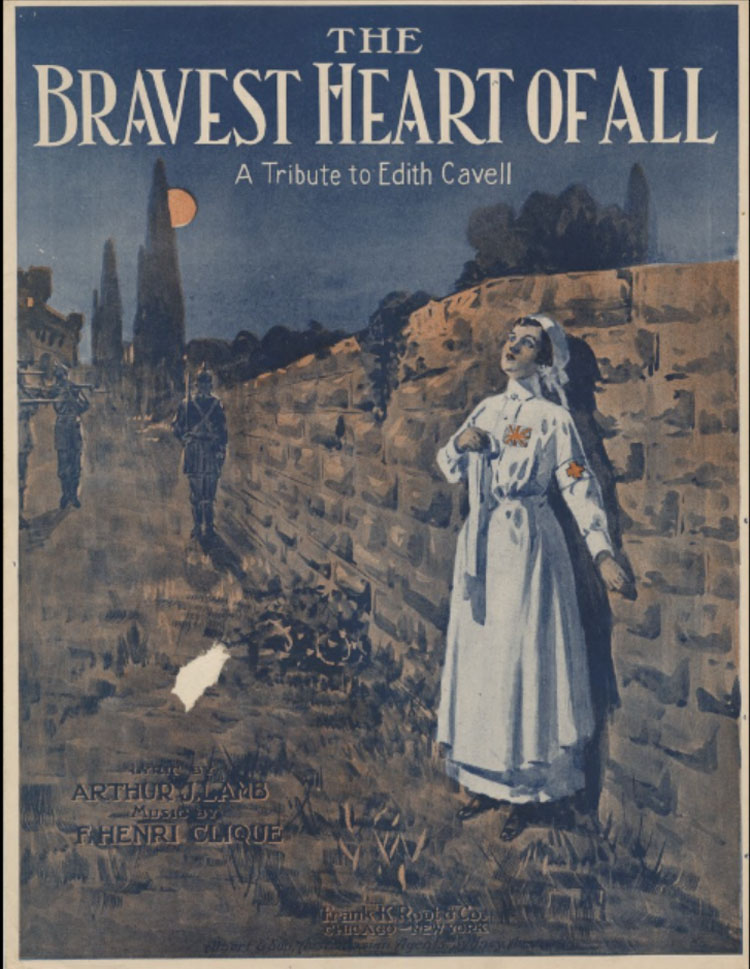

Edith Cavell

"The Bravest Heart of All - A Tribute

to Edith Cavell," by Lamb and Clique, Published by Frank K. Root

& Co., Chicago, 1915 (Courtesy

Northern Illinois University Digital Library, Lee Schreiner

Sheet Music Collection)

Leonard looked him over. "Good Lord,

Claude, you ain't the only fellow around here that wears pants!

What for? Well, I'll tell you what for," he held up three large

red fingers threateningly; "Belgium, the Lusitania, Edith Cavell.

That dirt's got under my skin. I'll get my corn planted, and then

Father'll look after Susie till I come back."

Claude took a long breath. "Well,

Leonard, you fooled me. I believed all this chaff you've been giving

me about not caring who chewed up who."

And no more do I care," Leonard

protested, "not a damn! But there's a limit. I've been ready to

go since the Lusitania. I don't get any satisfaction out of my place

any more. Susie feels the same way." (pp. 316-317).

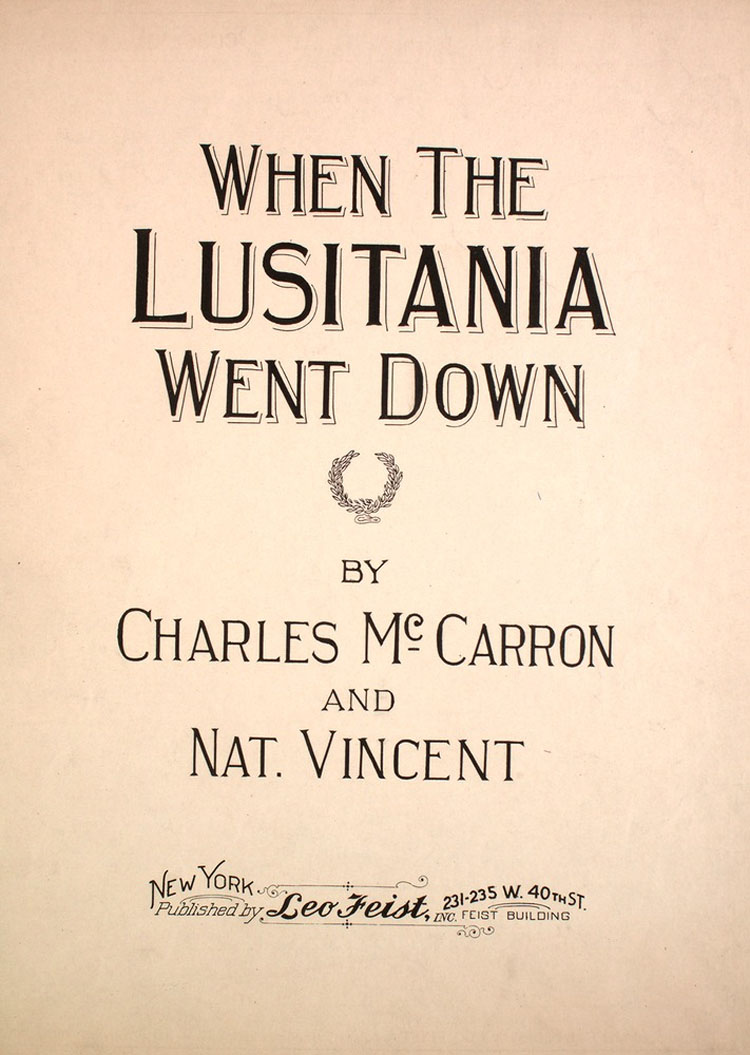

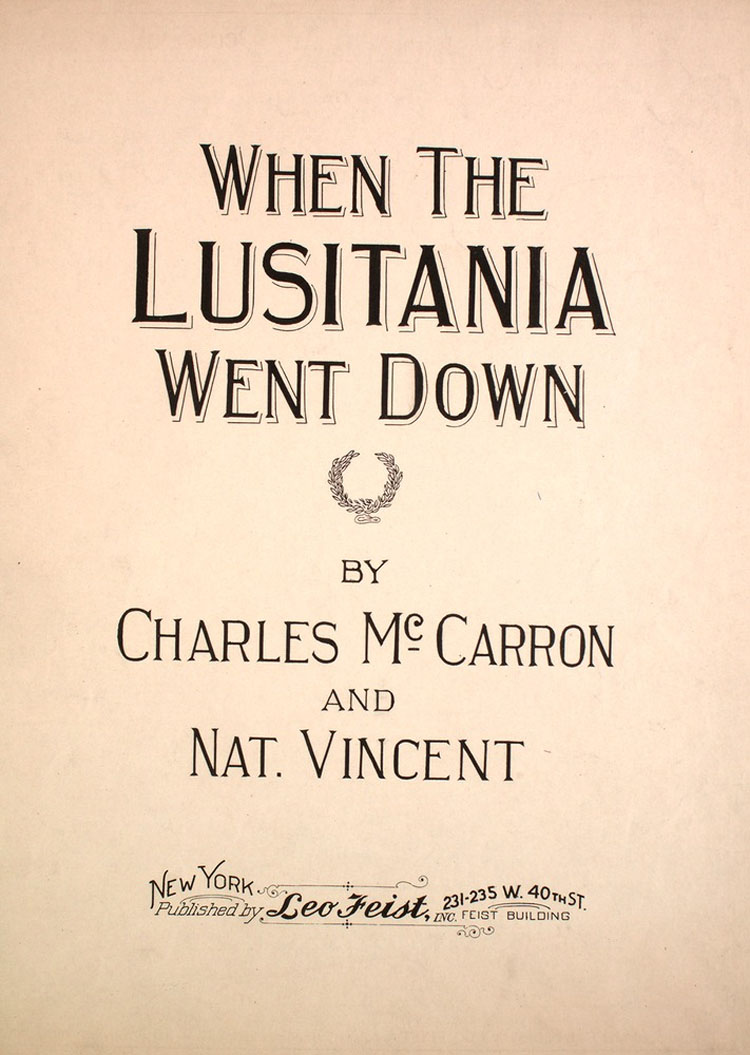

The Lusitania

When the Lusitania Went Down

by Charles McCarron and Nat. Vincent, Publisher Leo Feitst, New York,

1915. (Courtesy The

Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music)

"When the Lusitania Went Down"

Sung by Herbert Stuart, Columbia Record No. A1772, double-sided disc

recorded May 20, 1915 (Courtesy

i78s.org

and Internet

Archive)

(Sheet Music and record

courtesy of Giovannoni-Sheram Collection and i78s.org)

"Let's All Be Americans Now"

by Berlin, Leslie and Meyer; Published by Waterson, Berlin and Snyder,

New York, 1917 (Courtesy Duke

University Libraries - David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript

Library)

When the record "Let's All Be Americans

Now" was recorded on February 28, 1917 the United States had

not yet declared war. One of the lyrics of the song included the possibility

that "England or France may have your sympathy, -- or Germany."

But "now is the time" "Let's all be Americans Now."

"Now there's trouble in the

air, War is talked of ev'ry where,...We're not looking for any kind

of war, but if we fight we must

It's up to you! What will you do?

England or France may have your sympathy, -- or Germany

But you'll agree that, now is the

time, To fall in line...You swore that you would, so be true to

your vow, Let's all be Americans Now."

"Let's

All Be Americans Now" performed by Adolph J. Hahl (Arthur

Hall), Edison Domestic series 3201, 4-minute Edison Blue Amberol Record,

recorded February 28, 1917 (Courtesy of i78s.org

)

On February 1, 1917 Germany returned

to its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. On April 6, 1917

the United States declared war on Germany.

When war on Germany was declared by

the United States the phonograph industry responded with support,

patriotism, and related songs and thematic promotional material. Claude

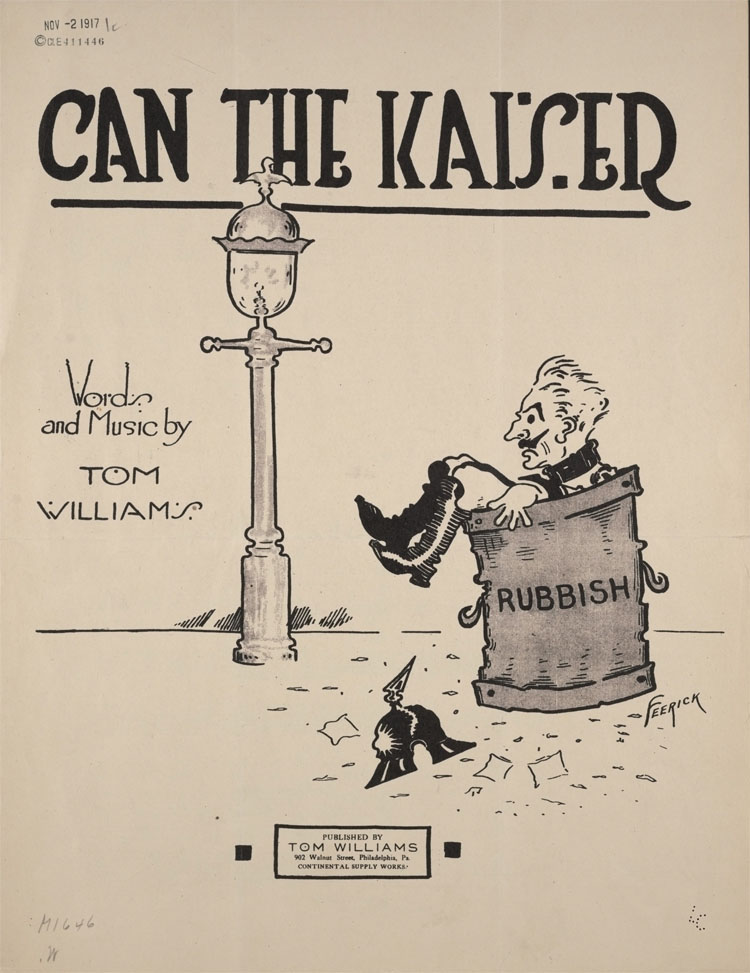

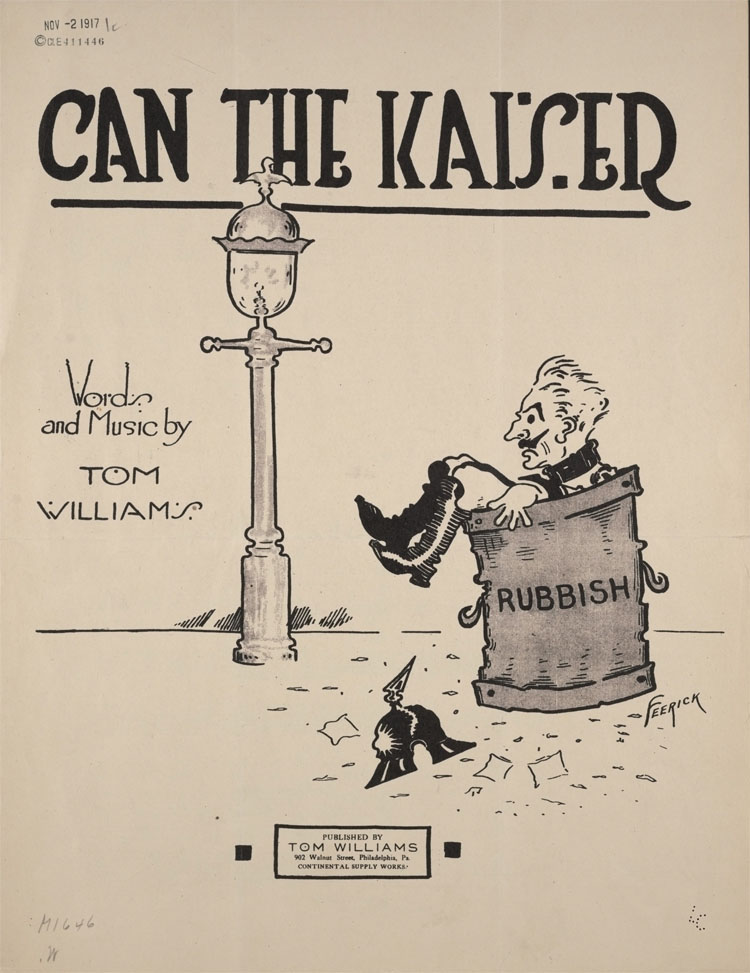

and his band of new brothers had a few thoughts about the Kaiser:

If they talked about the war, or

the enemy they were getting ready to fight, it was usually in a

facetious tone; they were going to "can the Kaiser," or to make

the Crown Prince work for a living. Claude loved the men he trained

with,—wouldn't choose to live in any better company. (p. 333)

Wanting to "make the Crown Prince

work for a living" was also expressed as wanting the Kaiser to

be in hock or "Hock the Kaiser" (as Bert

Williams sang in his record "I'm Neutral" when he said

"there ain't no use in talkin" but "somebody hocked

the Kaiser and I don't know the reason why."

"Can" the Kaiser and other

messages to the Kaiser

This motion toy phonograph attachment

featured Uncle Sam booting, kicking, and "canning" Kaiser

Bill who is running away carrying his U-Boat "Pretzel."

The National Toy Co., “Play

with any Lively or Patriotic Record.” The Talking Machine World,

May 1917

Watch

Uncle Sam "boot" Kaiser Bill to Sousa's "Under

the Double Eagle March" (30 second extract courtesy of CURIOSITYPHONO)

"Can the Kaiser" by Adkins

& Fennell, Published by Adkins-Fennell Music Co., Kansas City,

MO, 1917 (Courtesy Library of

Congress)

"They're on their way to Kan the

Kaiser" by Pyle and Thomas. Published by Thomas & O'Connell

Music Pub. Co., New York City, 1917 (Courtesy

The

Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music)

"Can the Kaiser, Yankees"

by Tom Williams, Published by Tom Williams, Philadelphia, PA, 1917

(Courtesy Library of Congress)

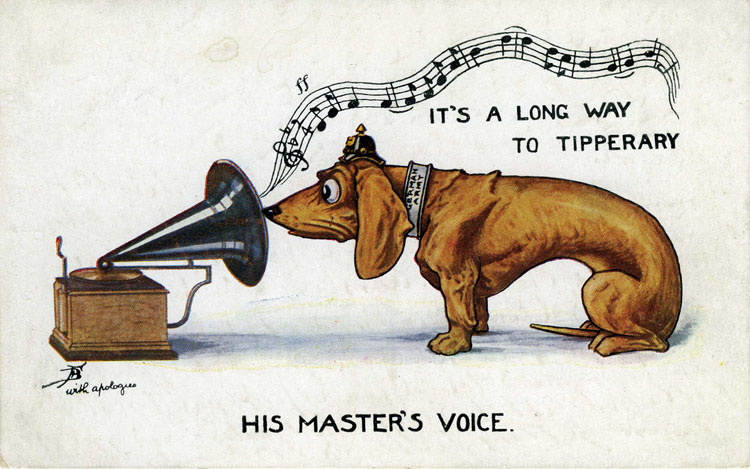

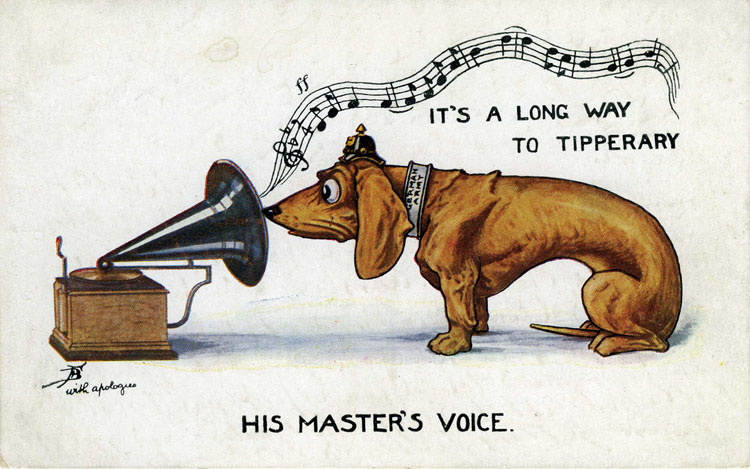

Nipper and "His Master's Voice"

were adapted into war-time parodies and propoganda.

Postcard circa 1917 (PM-2048)

Postcard circa 1914 (PM-0414)

Postcard circa 1916 (PM-0356)

THE DACHSHUND:

"I thought you were only a contemptible little talking machine."

(Source: The Bystander,

October 7, 1914, Mary

Evans Picture Library)

Political Cartoon published

in 1916 regarding Flemish newspaper purchased by Germany during World

War I (6A)

"His Master's Voice,"

April 20, 1918, US

National Archives, Berryman Political Cartoon Collection

The Montreal Daily Star, October

15, 1918 as reprinted in The Talking Machine World, November

15, 1918 depicting in a cartoon the recent correspondence between

President Wilson and the German Government regarding an armistice.

The Talking Machine

World, May 1917

"We're All Going Calling

on the Kaiser" by Caddigan and Brennan, publisher Leo. Feist, Inc.

New York (Courtesy of Giovannoni-Sheram

Collection i78s.org)

"We're

All Going Calling on the Kaiser" sung by Arthur Fields and

Peerless Quartette, Columbia Record A2569, Recorded May 13, 1918

(Courtesy of i78s.org)

Investigation of pro-German propaganda

using phonograph records

"Canned

Propaganda," The Talking Machine World, March 15,

1918

VALLORBES NEEDLES

"MOBILIZED

in the SERVICE of OUR COUNTRY"

The Talking Machine

World, June 15, 1918 (Click image to see full ad)

Cover of Trade Journal

The Voice of the Victor, October 1918.

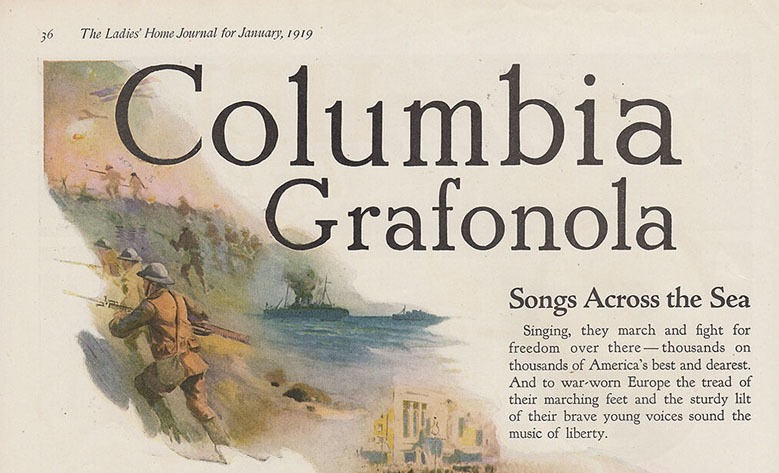

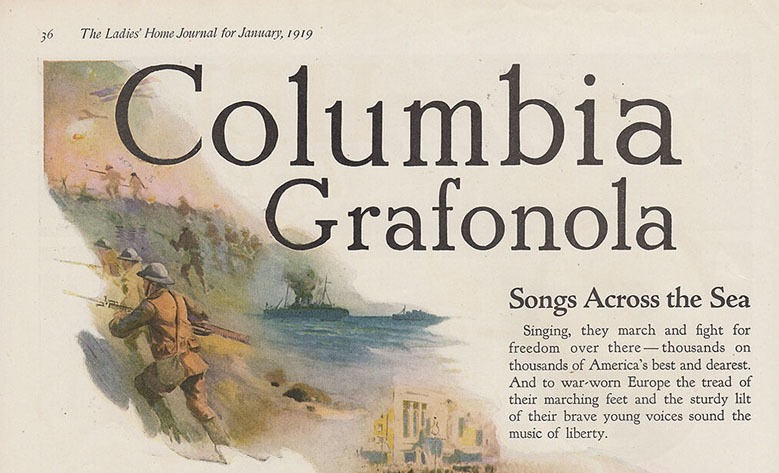

"Songs Across the Sea" and

the "the music of liberty." The Ladies' Home Journal

for January, 1919

Submarine Warfare

There are a number of references to

the German submarine threat and its impact on the war starting with

Germany's resumption of "unrestricted submarine warfare."

...indeed, until the announcement

that Germany would resume unrestricted submarine warfare made every

one look questioningly at his neighbour. (p. 304)

German submarine crew playing

music and listening to gramophone, postcard ca. 1915 (PM-0675)

Germany's announcement of unrestricted

warfare on all ships would be a major impetus for the United States

to finally enter the war. Once war was declared on Germany the former

neutrality and even support of Germany by Americans vanished and the

many of the German immigrants in Nebraska who were former friends

and neighbors were transformed into potential informants or saboteurs.

Literally reflecting this change of heart, names of cities and businesses

were changed. Historian Jim McKee summarizes some of these changes

in Nebraska as follows:

Lincoln's German-American Bank

became Continental National Bank, Schmidts became Smiths, Gov. Charles

Dietrich's German National Bank of Hastings became the Nebraska

National Bank, while the town of Berlin became Otoe and Germantown

in Seward County was renamed Garland for Ray Garland, who was killed

in France in 1918. (4)

McKee then notes that

"in the hasty renaming of Berlin, it was probably not even named

in honor of the German city but for E.D. Berlin, a local farmer.

This 1918 era photo shows a Lincoln

parade with its obvious anti-German sentiments illustrated in the

"To hell with the the bier-like wagon saying, "Liberty Day." Jim

McKee, The Lincoln Journal, June 27, 2010 (Photo courtesy

of Kent Remenga).

Submarine Warfare (Continued)

Description from the Edison record

sleeve of Edison Record No. 50490, Submarine Attack (Courtesy

of i78s.org)

Submarine

Attack by Theodore Morse

performed by Premier Quartet and Company, Edison Diamond Disc Re-Creation

Record No. 50490 (Courtesy of i78s.org)

"The

Submarine Attack Somewhere

at Sea" Sung

by Peerless Quartette, Columbia Grafonola A2626, Recorded February

27, 1918 (Courtesy Library of

Congress)

"Good Bye Kaiser Bill" by

J. L. Waldorf, Published by J. L. Waldorf,, Centerburg, OH 1918 (Courtesy

Library of Congress)

Additional references to German submarines

in One of Ours.

"Here's one naval authority

who says the Germans are turning out submarines at the rate of three

a day. They probably didn't spring this on us until they had enough

built to keep the ocean clean." (p. 306)

A second witness had heard Oberlies

say he hoped the German submarines would sink a few troopships;

that would frighten the Americans and teach them to stay at home

and mind their own business. (p.

321)

Claude's mother was extremely anxious

about Claude and the other soldiers being able to safely cross the

ocean because of the German submarines.

"I hardly see how we can bear the

anxiety when our transports begin to sail," she said thoughtfully.

"If they can once get you all over there, I am not afraid; I believe

our boys are as good as any in the world. But with submarines reported

off our own coast, I wonder how the Government can get our men across

safely. The thought of transports going down with thousands of young

men on board is something so terrible—" she put her hands quickly

her eyes. (pp. 341-342)

"Absolutely. The British are depending

on their aircraft designers to do just that, if everything else

fails. Of course, nobody knows yet how effective the submarines

will be in our case." (p. 343)

"Lieutenant, I wish you'd explain

Lieutenant Fanning to me. He seems very immature. He's been telling

me about a submarine destroyer he's invented, but it looks to me

like foolishness."(p. 365)

In popular culture one of the three

World War I patriotic "Talking Books" put out in June 1919

by the Talking Book Corporation was "Submarine Attack."

The Talking Machine

World, June 15, 1919

The Talking Book Corporation was one

of the companies owned by Victor Hugo Emerson who was the founder

of the Emerson Phonograph Company and Emerson

Records. Violinist David Hochstein recorded for Emerson Records.

Submarine Attack

- A "Talking" Book

Submarine Attack A "Talking"

Book made by The Talking Book Corporation, Emerson Records, 1919

(FP1286)

The book is opened and the book's page

with the record on it is placed on the phonograph's platter. Listen

to SUBMARINE ATTACK on this record.

The Talking Book Corporation, Emerson

Records, 1919 (Video courtesy of Bruce

Victrolaman Young)

Submarine Attack A "Talking"

Book (back cover)

Submarine Attack a

"Talking" Book page 2 (FP1286A)

We'll knock that little "U-boat"

high and dry, words by

Alice D. Elfreth, Music by Al. Franz, Published by Alice D. Elfreth,Philadelphia,

Pa., 1917, monographic. (Courtesy

Library

of Congress)

The Marne

The Allied success at the First Battle

of the Marne in 1914 saved Paris from being taken by the Germans.

Marne is referenced throughout the book for its strategic victory

but also for its lasting memory as its name "had come to have

the purity of an abstract idea" and everyone in France seemed

to have a connection to it.

Claude squirmed, as he always did

when his mother touched upon certain subjects. "Well, you see, I

can't forget that the Germans are praying, too. And I guess they

are just naturally more pious than the French." Taking up the book

he began once more: "In the low ground again, at the narrowest part

of the great loop of the Marne," etc. (p. 230)

"The French have stopped falling

back, Claude. They are standing at the Marne. There is a great battle

going on. The papers say it may decide the war. It is so near Paris

that some of the army went out in taxi-cabs." (p. 231)

It was curious, he reflected, lying

wide awake in the dark: four days ago the seat of government had

been moved to Bordeaux,—with the effect that Paris seemed suddenly

to have become the capital, not of France, but of the world! He

knew he was not the only farmer boy who wished himself tonight beside

the Marne. The fact that the river had a pronounceable name, with

a hard Western "r" standing like a keystone in the middle of it,

somehow gave one's imagination a firmer hold on the situation. Lying

still and thinking fast, Claude felt that even he could clear the

bar of French "politeness"—so much more terrifying than German bullets—and

slip unnoticed into that outnumbered army. One's manners wouldn't

matter on the Marne tonight, the night of the eighth of September,

1914. There was nothing on earth he would so gladly be as an atom

in that wall of flesh and blood that rose and melted and rose again

before the city which had meant so much through all the centuries—but

had never meant so much before. Its name had come to have the purity

of an abstract idea. In great sleepy continents, in land-locked

harvest towns, in the little islands of the sea, for four days men

watched that name as they might stand out at night to watch a comet,

or to see a star fall. (pp. 232-233)

As she went about these tasks, she

prayed constantly. She had not prayed so long and fervently since

the battle of the Marne. (p. 249)

Yet here they were. And in this

massing and movement of men there was nothing mean or common; he

was sure of that. It was, from first to last, unforeseen, almost

incredible. Four years ago, when the French were holding the Marne,

the wisest men in the world had not conceived of this as possible;

they had reckoned with every fortuity but this. Out of these stones

can my Father raise up seed unto Abraham. (p. 377)

Something was released that had

been struggling for a long while, he told himself. He had been due

in France since the first battle of the Marne; he had followed false

leads and lost precious time and seen misery enough, but he was

on the right road at last, and nothing could stop him. (p. 412)

And her father? He was dead; mort

è la Marne, en quatorze. "At the Marne?" Claude repeated, glancing

in perplexity at the nursing baby. (p. 476)

When Owens was in college he had

never shown the least interest in classical studies, but now it

was as if he were giving birth to Caesar. The war came along, and

stopped the work on his dam. It also drove other ideas into his

exclusively engineering brains. He rushed home to Kansas to explain

the war to his countrymen. He travelled about the West, demonstrating

exactly what had happened at the first battle of the Marne, until

he had a chance to enlist.

In the Battalion, Owens was called

"Julius Caesar," and the men never knew whether he was explaining

the Roman general's operations in Spain, or Joffre's at the Marne,

he jumped so from one to the other. Everything was in the foreground

with him; centuries made no difference. Nothing existed until Barclay

Owens found out about it. (pp. 486-487)

Claude thought he would stroll about

to look at the town a little. It had been taken by the Germans in

the autumn of 1914, after their retreat from the Marne, and they

had held it until about a year ago, when it was retaken by the English

and the Chasseurs d'Alpins . They had been able to reduce it and

to drive the Germans out, only by battering it down with artillery;

not one building remained standing. (p. 500)

He told her about his mother and

his father and Mahailey; what life was like there in summer and

winter and autumn—what it had been like in that fateful summer when

the Hun was moving always toward Paris, and on those three days

when the French were standing at the Marne; how his mother and father

waited for him to bring the news at night, and how the very cornfields

seemed to hold their breath.

Mademoiselle Olive sank back wearily

in her chair. Claude looked up and saw tears sparkling in her brilliant

eyes. "And I myself," she murmured, "did not know of the Marne until

days afterward, though my father and brother were both there! I

was far off in Brittany, and the trains did not run. (p. 513)

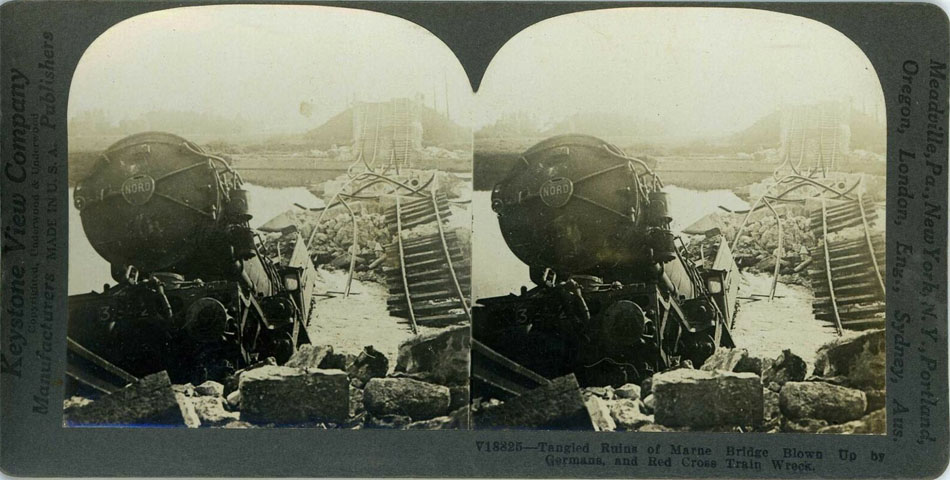

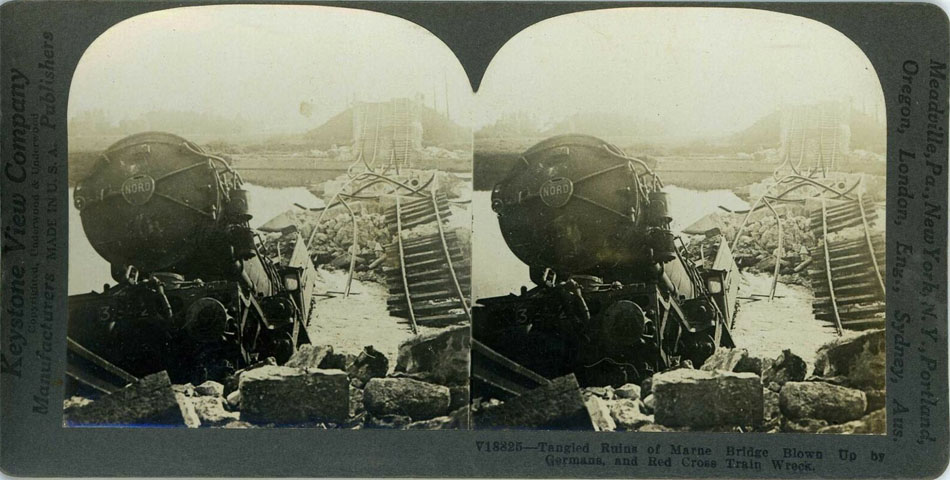

Stereoview card published 1919. Ruins

of Marne Bridge. After the Germans were defeated on the Marne in 1914

they blew up this bridge in their "hasty retreat to hamper the

pursuing French."

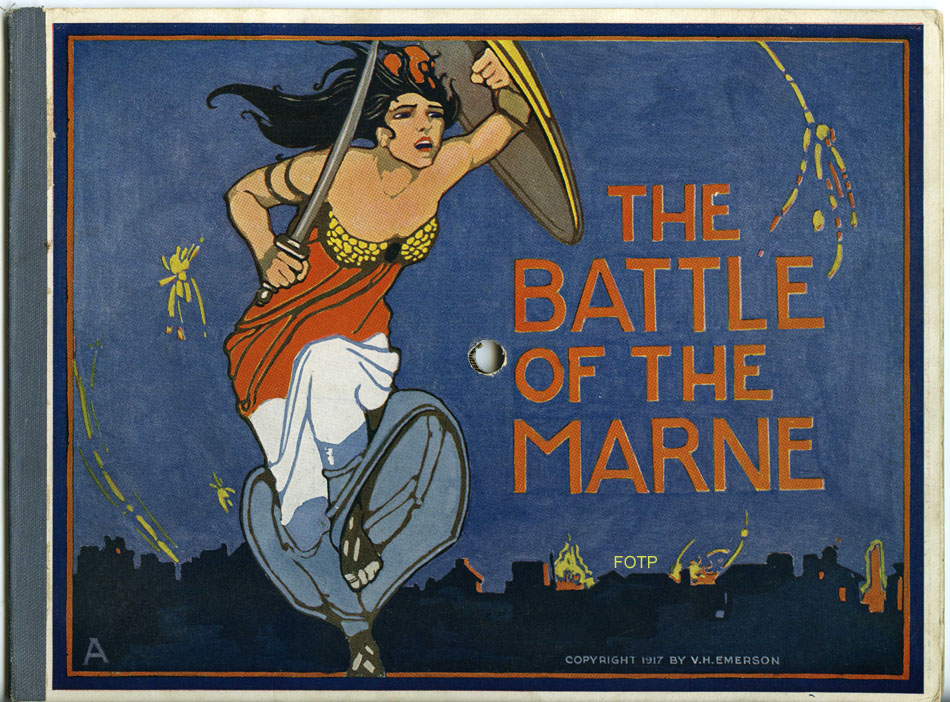

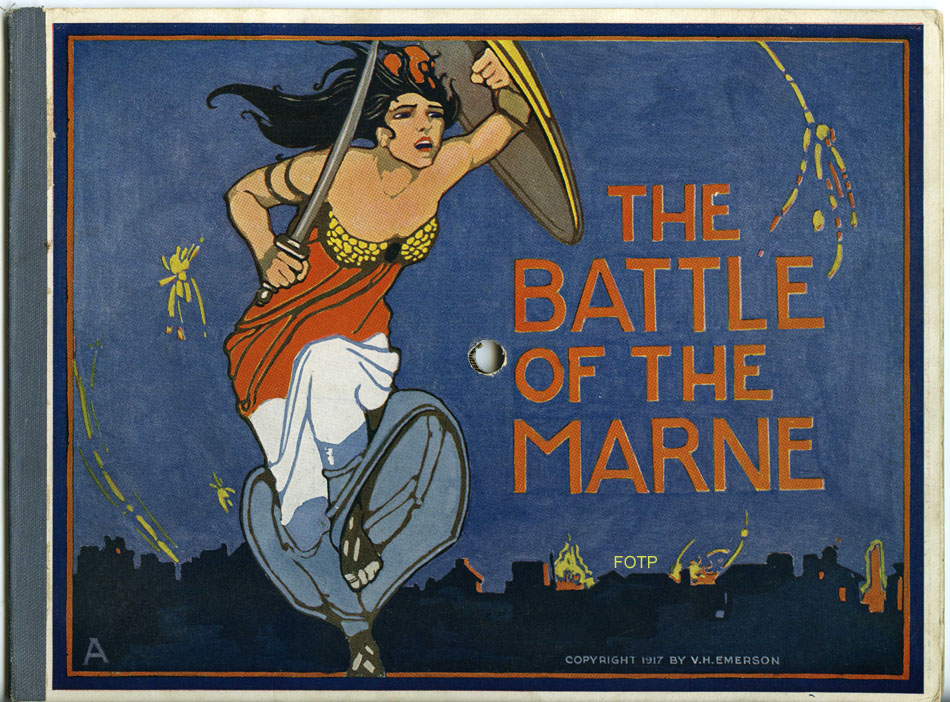

The Battle of the Marne - A

"Talking" Book, by V. H. Emerson and the Talking Book

Corporation, 1917 (FP1480)

The Battle of the Marne - A "Talking"

Book, by V. H. Emerson and the Talking Book Corporation, 1917 (FP1480)

The Battle of the Marne - A "Talking"

Book, by V. H. Emerson and the Talking Book Corporation, 1917 (FP1480)

"Let us listen

to the Story! Let us sing the Marseillaise!"

La Mareillaise by Etienne Drian in Gazette

du bon ton: Arts, modes & frivolités. Paris:

Lucien Vogel, Summer 1915. La Marseillaise illustration and

the following text are from En Guerre, French Illustrators and

World War I by Neil Harris and Teri J. Edelstein, University of

Chicago Library, 2014, p. 102)

An editorial in the Gazette du

bon ton in the summer of 1915 declared "that because France

has just escaped the greatest peril and is proceeding toward certain

victory, the magazine could be published." The authors then

noted that "most of the illustrations contain no hint of war."

However, a series by Etienne Drian did: "Fashionably dressed

women engage in patriotic activities: arranging a tricolor bouquet,

reading the war news, following a battle map, or listening to the

Marseillaise."

"La

Marseillaise" (de Lisle) {In English}, performed by Thomas

Chalmers, Edison Concert series 28289, 4-minute Edison Blue Amberol

Record, recorded May 21, 1917 (Courtesy i78s.org)

"The Marseillaise is worth

a million men to France."

Edison Message No. 26,

The Talking Machine World, September 15, 1918

Battle of the Marne War Song

"They Shall Not Pass (Battle of

the Marne War Song)" Sheet

music contributor names Schasberger, Otto C. (composer) Muchmore,

Henry E. (lyricist) Published by Music Printing Co., New York, 1918

(Courtesy Library of Congress)

"Battle of the Marne March"

by J. Luxton, published by Church,

Paxson, & Co., New York, 1916 (Courtesy

Smithsonian

Libraries)

"Battle

of the Marne March" by J. Luxton on 4-minute Edison Amberola

Record No. 3018 performed by Sodero's Band (as New York Military Band)

Cesare Sodero, director, recorded April 20, 1916 (Courtesy i78s.org)

"Battle

of the Marne" Descriptive by J. Luxton played by the New

York Military Band on Edison Diamond Disc Record 50422, 1917 and available

on Internet

Archive.

"The

Battle of the Marne" performed by Russell Hunting, Elocutionist,

on Pathe 12" Record No. 35067, double-sided disc (Courtesy of

i78s.org)

"We

stopped them at the Marne," performed by Premier Quartet

, Edison Domestic series 3525, 4-minute Edison Blue Amberol Record,

recorded April 23, 1918 (Courtesy of i78s.org)

"Spirit of France March" by

E. T. Paull, Published by E. T.

Paull Music Co., New York, 1919

Foch's Message to Joffre at the Battle

of the Marne: "My right

wing is retreating. My left wing is broken, I am attacking with the

center." (Courtesy The

University of South Carolina and the Joseph M. Bruccoli Great

War Collection)

Claude Prepares for France

Claude had studied French in school

and thought he knew it well enough to even be able to slip into their

army to help save Paris if he would have been in France at the time.

And when he did enlist and finished his basic training and was going

home before shipping off to France he would continue to study his

French. Most of the American doughboys didn't know French. The French

phrase book "made up of sentences chosen for their usefulness

to soldiers" was one solution.

"I surely never wore anything else

in the month of July," Claude admitted. "When I find myself riding

along in a train, in the middle of harvest, trying to learn French

verbs, then I know the world is turned upside down, for a fact!"

The old man pressed a cigar upon him and began to question him.

Like the hero of the "Odyssey" upon his homeward journey, Claude

had often to tell what his country was, and who were the parents

that begot him. He was constantly interrupted in his perusal of

a French phrase book (made up of sentences chosen for their usefulness

to soldiers,—such as, "Non, jamais je ne regarde les femmes") by

the questions of curious strangers. (pp. 326-327)

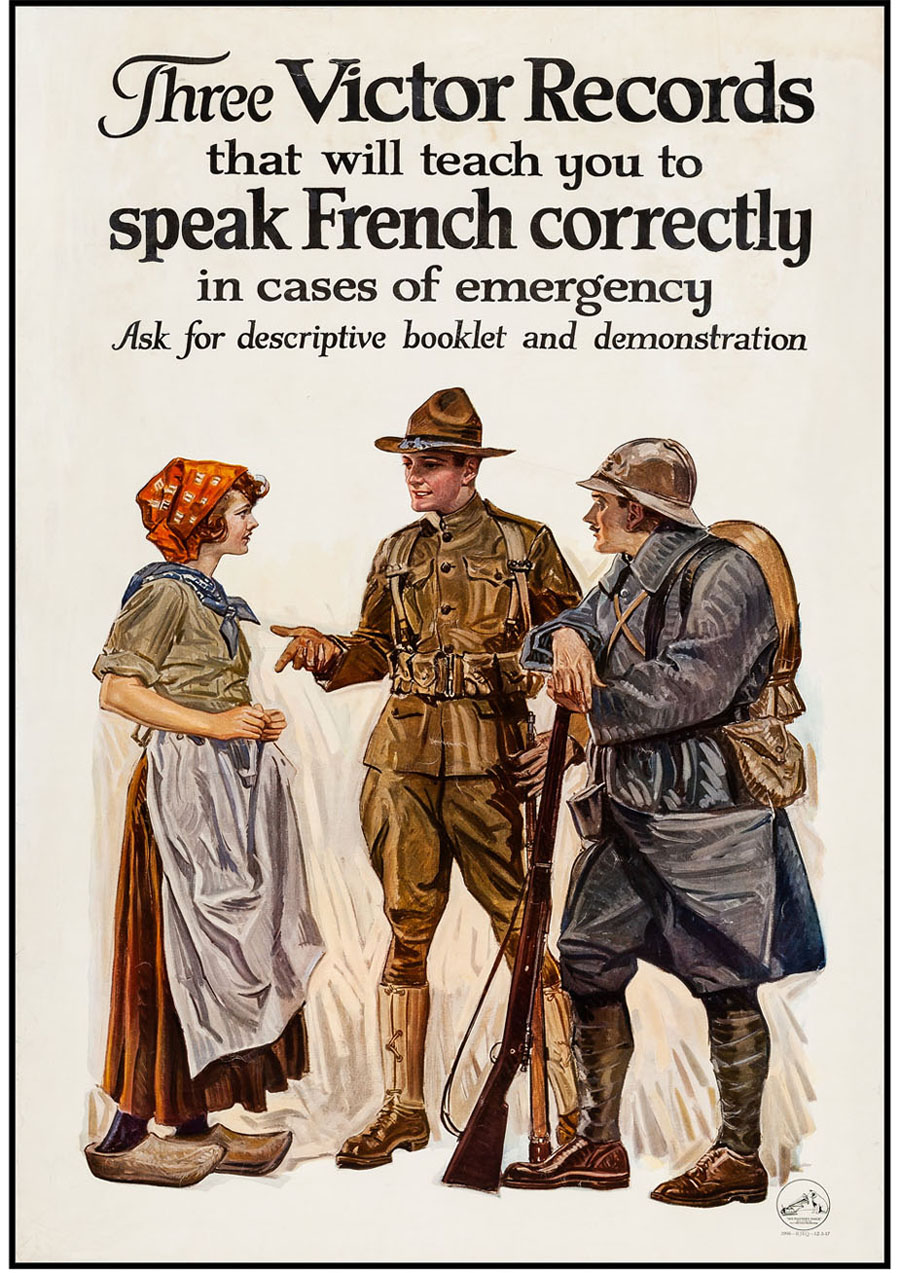

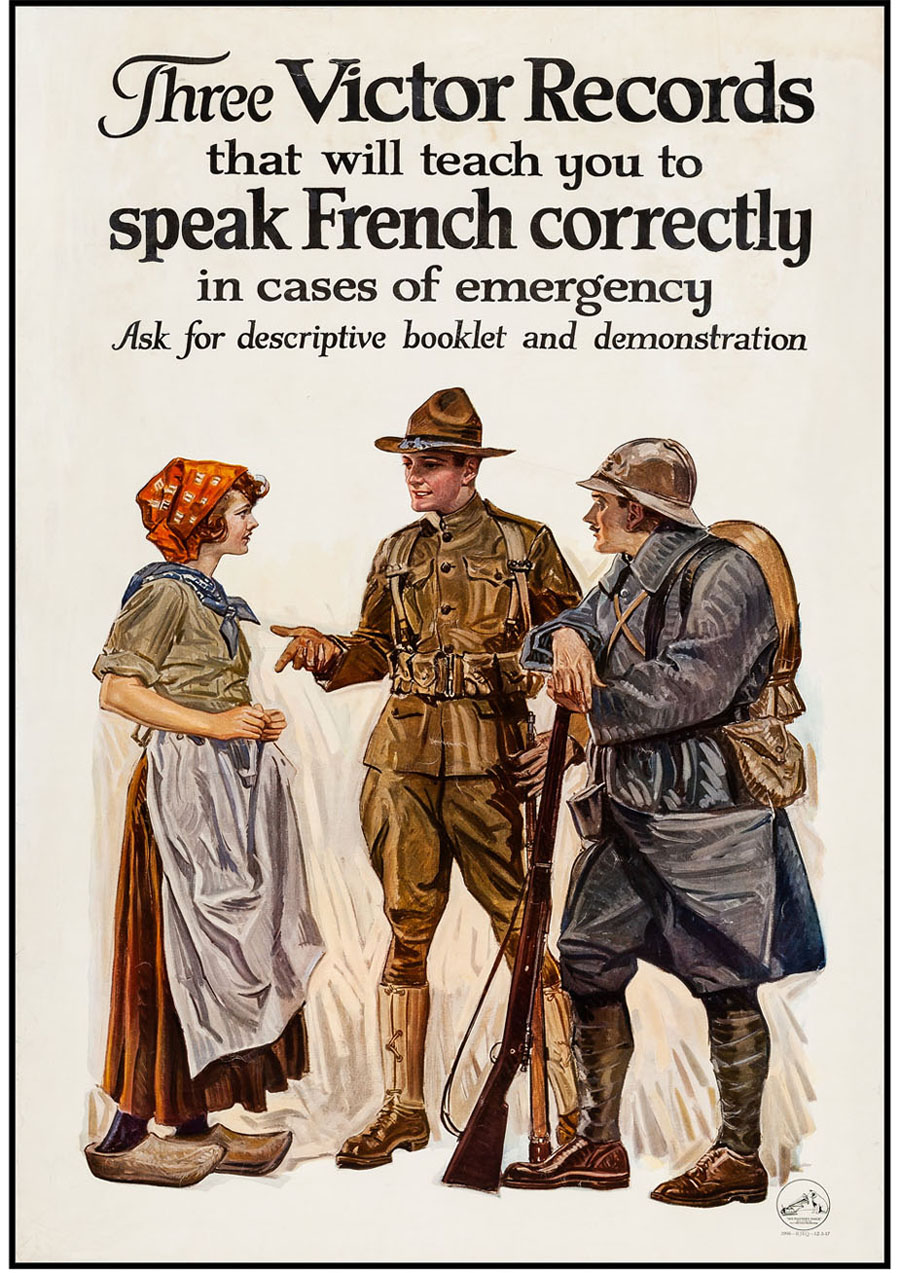

The phonograph industry offered another

way "for the use of Army Men in France besides a French phrase

book:" French language courses, e.g., Cortina's Phone-Method,

Victor's French Record Course, and others.

The Talking Machine

World, August 1917, p. 111

"Victor French Course in Demand

- Represents a Timely Contribution to the War Needs of the Country

From the Talking Machine Trade — Being Strongly Featured," headline

of article in The Talking Machine World, January

1918, p. 68

Original Poster (24.75"

X 37") Courtesy of Heritage

Auctions ©2018

When

Yankee Doodle Learns to "Parlez Vous Francais," by Hart

& Nelson, A.J. Stasny Music Co., New York, 1917

When

Yankee Doodle Learns to "Parlez Vous Francais,"

sung by Arthur Fields, 4-minute

Edison Amberola Record No. 3447, Recorded on December 4, 1917 (Courtesy

i78s.org)

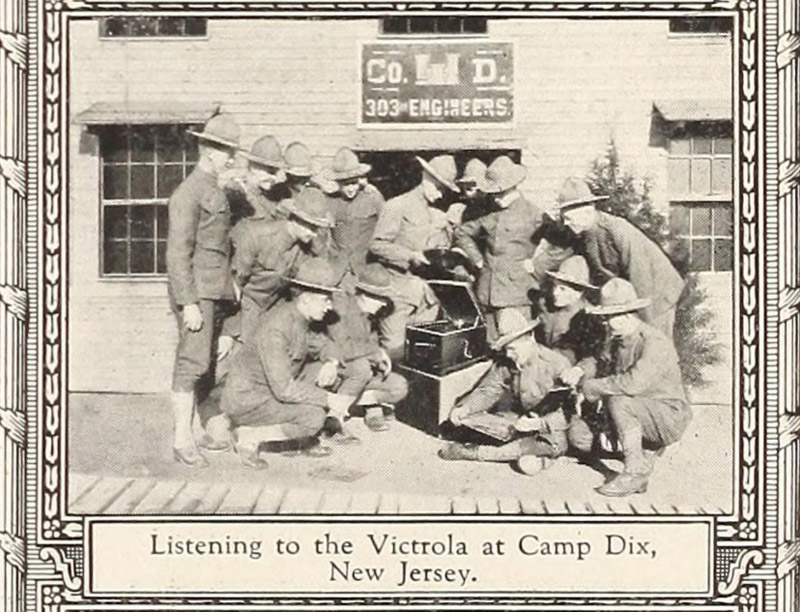

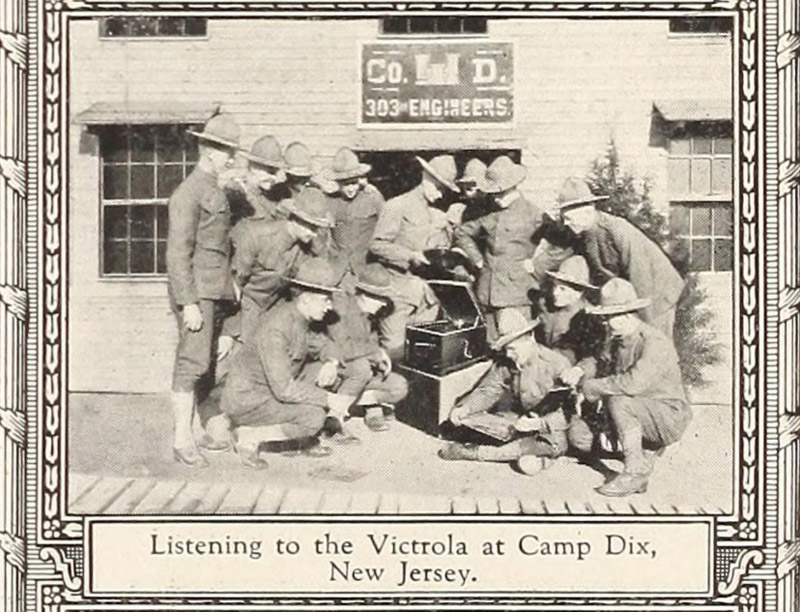

Camp Dix, New Jersey

Gerhardt rolled over on his back

and put his hands under his head. "Oh, this affair is too big for

exceptions; it's universal. If you happened to be born twenty-six

years ago, you couldn't escape. If this war didn't kill you in one

way, it would in another." He told Claude he had trained at Camp

Dix, and had come over eight months ago in a regimental band, but

he hated the work he had to do and got transferred to the infantry.

(p. 466)

David Gerhardt trained at Camp Dix and

played in regimental band.

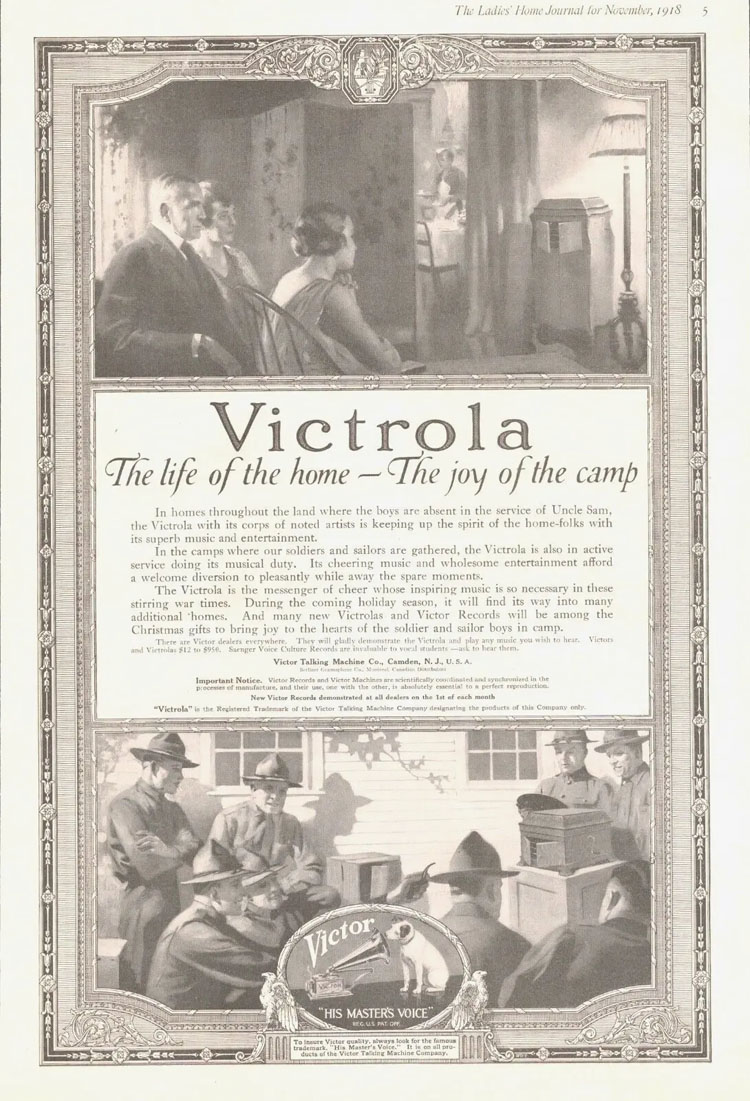

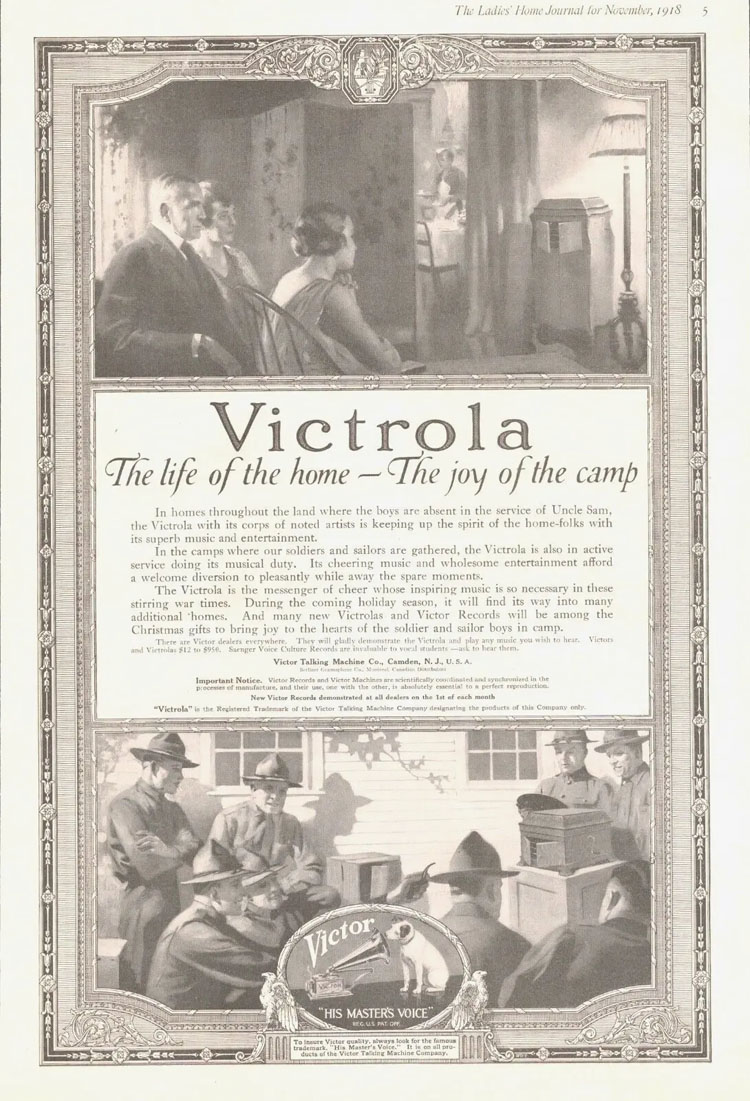

Listening to the Victrola

at Camp Dix, New Jersey

"In Camp or Trench, on transport

or battleship...the Victrola is the unflagging, and often the only

source of music and entertainment." The

Talking Machine World, July 15, 1918

Dutch Officers listening to the phonograph.

RPPC ca.1915 (PM-0369) The Netherlands remained neutral throughout

World War I.

Life in the U. S. Army

Cantonment. Postcard ca.1918 (PM-0368)

Gathering Around the Phonograph.

Postcard ca.1919 (PM-0357)

"The Victrola is in active service

doing its musical duty..bringing joy to the hearts of the soldier

and sailor boys in camp." The Ladies' Home Journal, November

1918 (PM-2138)

"Good Bye Broadway, Hello France"

The National Geographic

Magazine, February 1918

As Claude and the troops stood on the

deck of their ship leaving the port of New York City Claude saw its

profile in the mist and there was disappointment as the tall buildings

"looked unsubstantial and illusionary' and no one knew what buildings

they were even looking at. They didn't get their day in the city and

now they were leaving for Paris and had "never so much as walked

up Broadway."

By seven o'clock all the troops

were aboard, and the men were allowed on deck. For the first time

Claude saw the profile of New York City, rising thin and grey against

an opal-coloured morning sky. The day had come on hot and misty.

The sun, though it was now high, was a red ball, streaked across

with purple clouds. The tall buildings, of which he had heard so

much, looked unsubstantial and illusionary,—mere shadows of grey

and pink and blue that might dissolve with the mist and fade away

in it. (p. 361)

They agreed it was a shame they

could not have had a day in New York before they sailed away from

it, and that they would feel foolish in Paris when they had to admit

they had never so much as walked up Broadway. (p. 361)

"Good-Bye Broadway, Hello France"

by Reisner and Davis, Music by Baskette, Published by Leo. Feist,

Inc., New York 1917 (Courtesy

of i78s.org)

"Good

Bye Broadway, Hello France" Sung by Peerless Quartette, Columbia

Record A2333, Recorded on July 16, 1917 in New York City. (Courtesy

Library of Congress)

"Good

Bye Broadway, Hello France" Sung by Arthur Fields. Edison

Domestic Series 3321, 4-minute celluoid cylinder, recorded July 17,

1917 (also dubbed on Edison Diamond Disc Record). (Courtesy

of i78s.org)

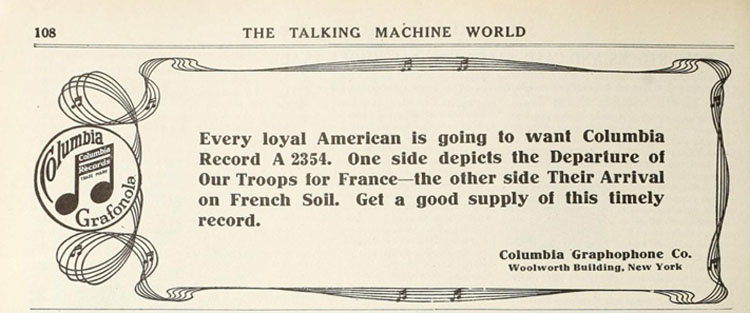

"Departure

of the American Troops for France" by Prince's Band and Columbia

Male Quartette Record A2354 (Courtesy

of i78s.org) and the Internet

Archive)

"Departure

of the First U.S. Troops for France" by Russell Hunting,

Pathé 20125 (Courtesy of

i78s.org)

"When Alexander Takes His Ragtime

Band to France," by Bryan, Hess & Leslie, Published by Waterson,

Berlin & Snyder Co., 1918 (Giovannoni-Sheram Collection)

"When

Alexander Takes His Ragtime Band To France" by Marion Harris,

Victor Record No. 18486-A, 1918 (Courtesy of i78s.org)

The Statue of Liberty

Claude and the troops stood on the deck

of their ship leaving New York City and "sliding down toward

the point and getting their "first glimpse of the Bartholdi statue:"

"There she is!" "Hello, old girl!"

"Good-bye, sweetheart!"

The swarm surged to starboard. They

shouted and gesticulated to the image they were all looking for,—so

much nearer than they had expected to see her, clad in green folds,

with the mist streaming up like smoke behind. For nearly every one

of those twenty-five hundred boys, as for Claude, it was their first

glimpse of the Bartholdi statue. Though she was such a definite

image in their minds, they had not imagined her in her setting of

sea and sky, with the shipping of the world coming and going at

her feet, and the moving cloud-masses behind her. Post-card pictures

had given them no idea of the energy of her large gesture, or how

her heaviness becomes light among the vapourish elements. "France

gave her to us," they kept saying, as they saluted her. (p. 362)

"L-i-b-e-r-t-y" by Ted S.

Barron, published by Metropolis Music Co., New York, 1916 (Courtesy

Duke University Libraries)

"L-i-b-e-r-t-y"

by Henry Burr, Rex 10" Record No. 5377-A, produced 1914-1917

(Courtesy of i78s.org)

The Talking

Machine World, November 1917

"Over There"

Claude and the troops standing on the

deck of their ship leaving the port of New York City:

Before Claude had got over his first

thrill, the Kansas band in the bow began playing "Over There." Two

thousand voices took it up, booming out over the water the gay,

indomitable resolution of that jaunty air. (p. 363)

"Over

There" by Enrico Caruso, Victor Record 87294, recorded on

July 11, 1918 (Courtesy of i78s.org)

(Courtesy of i78s.org)

"OVER THERE" U.S. Navy

Recruitment Poster by Albert Sterner 1917. Sailor being sent to battle

by a symbolic female figure with sword, possibly Liberty. (Library

of Congress)

The Voyage of the Anchises

- "Long, Long Ago"

That evening Claude was on deck,

almost alone; there was a concert down in the ward room. To the

west heavy clouds had come up, moving so low that they flapped over

the water like a black washing hanging on the line. p. 376

The music sounded well from below.

Four Swedish boys from the Scandinavian settlement at Lindsborg,

Kansas, were singing "Long, Long Ago." Claude listened from a sheltered

spot in the stern. What were they, and what was he, doing here on

the Atlantic? p. 376

"Long, Long Ago": This nostalgic English

popular song was written by Thomas Harnes Bayly and was first published

as "The Long Ago" in 1833. (Explanatory Note 376, One of Ours

Scholarly Edition)

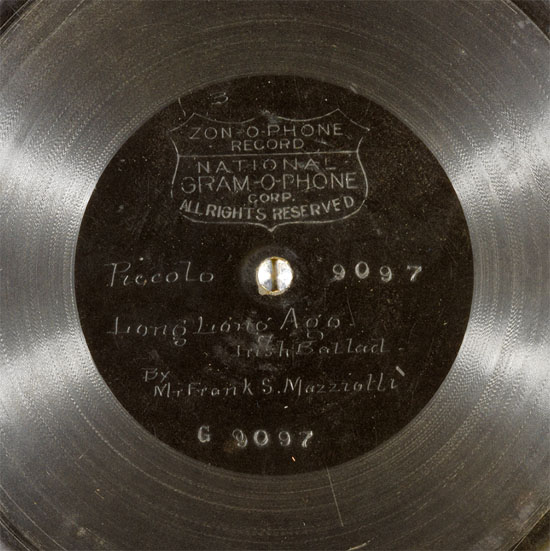

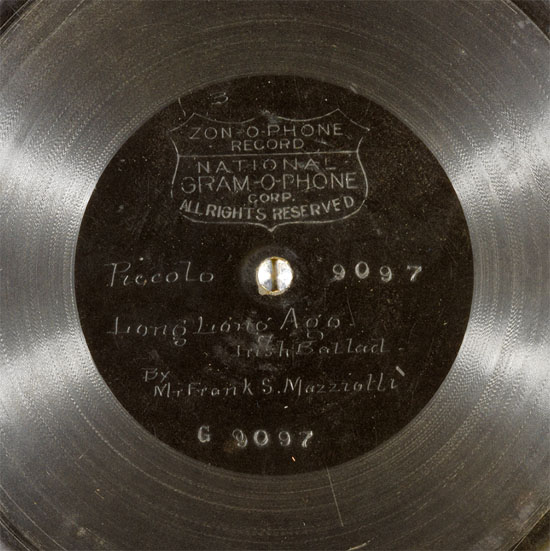

"Long,

Long Ago" Irish Ballad by Mr. Frank S. Maszziotti, Piccolo,

7" Disc Zon-o-phone Record 9097 (pre-1903)

"Long,

Long Ago" by Frieda Hempel, Recorded 12/31/1917, New York,

Edison 82550 10-in. (UCSB Library, DAHR)

The Voyage of the Anchises

- "Annie Laurie"

Downstairs the men began singing

"Annie Laurie." Where were those summer evenings when he used to

sit dumb by the windmill, wondering what to do with his life? p.

377

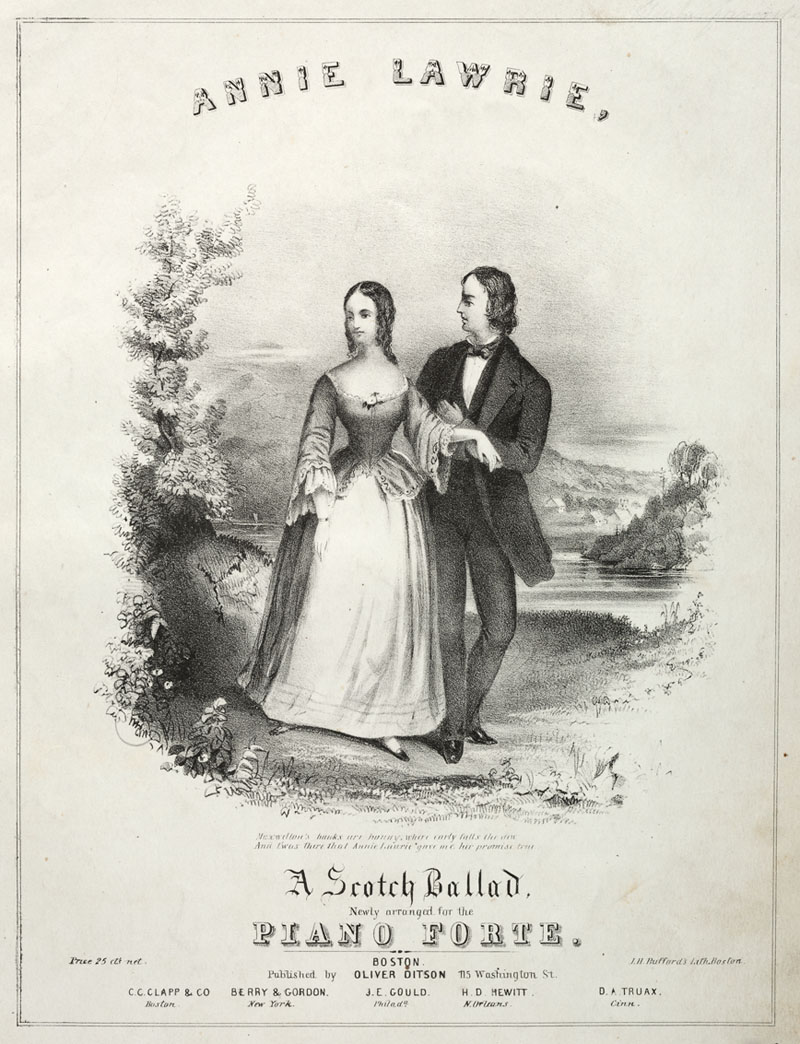

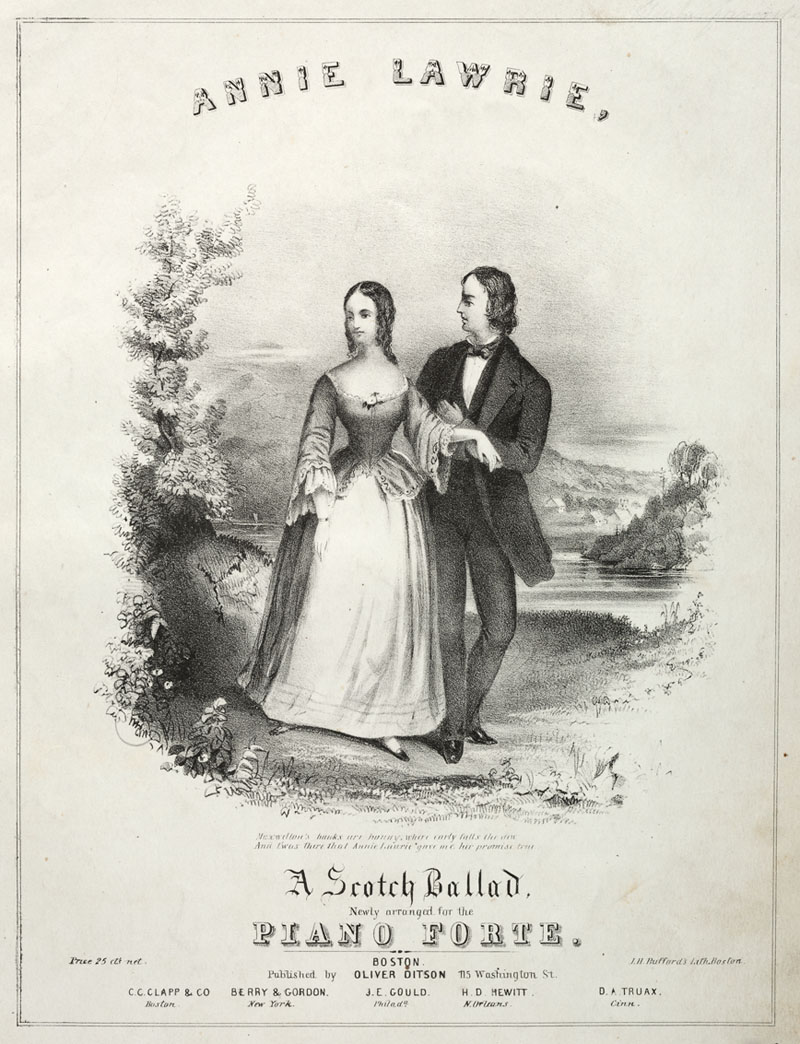

"Annie Laurie": This popular nineteenth-century

song by Lady John Dunlop Scott was based on a poem by William Douglas.

The verses express the sadness of lost love, as the speaker has discovered

that Annie has married another man. (Explanatory Note 377, One

of Ours Scholarly Edition)

"Annie Laurie"

sheet music cover, unknown date (Courtesy Cleveland

Museum of Art)

"Annie

Laurie" sung by Louise Homer, Victor Red Seal Record 87206,

Recorded 5/27/1914 Camden, New Jersey (i78s.org) (Label Courtesy Stanford

Libraries)

"They All Sang Annie Laurie,"

Words by J. Will Callahan, Music by F. Henri Klickmann, Publisher

Frank K. Root & Co., New York, 1915

Claude's Ship Arrives in France

Something caught his eye through

the porthole,—a great grey shoulder of land standing up in the pink

light of dawn, powerful and strangely still after the distressing

instability of the sea. Pale trees and long, low fortifications

. . . close grey buildings with red roofs . . . little sailboats

bounding seaward . . . up on the cliff a gloomy fortress. He had

always thought of his destination as a country shattered and desolated,—"bleeding

France"; but he had never seen anything that looked so strong, so

self-sufficient, so fixed from the first foundation, as the coast

that rose before him. It was like a pillar of eternity. The ocean

lay submissive at its feet, and over it was the great meekness of

early morning. (p. 422)

The Talking Machine

World, October 1917

"Arrival

of the American Troops in France" by Prince's Band and Columbia

Male Quartette Record A2354 (Courtesy of i78s.org)

and the Internet

Archive)

"The

Americans Come!" by Reinald Werrenrath, Victor Record 45157-A,

Recorded October 28, 1918 (Courtesy

of i78s.org)

Visit

BritishPathé to watch Arrival of American Troops In France

1917 - ©PATHE

Barricade in Streets

of Eclusiers, France. Stereoview card 1918 (PM-1886)

"Roses of Picardy"

With Victor and Claude having dinner

at the Grand Hotel in Dieppe, France, and with Victor heading out

to Verdun the next day, Victor is gloomy when answering about when

he'll next see Maisie in London, and starts whistling "Roses

of Picardy."

God knows," Victor answered gloomily.

He looked up at the ceiling and began to whistle softly an engaging

air. "Do you know that? It's something Maisie often plays; 'Roses

of Picardy.' You won't know what a woman can be till you meet her,

Wheeler." (p. 436)

"Roses

of Picardy "Sung by John McCormack, Victrola Red Seal Record

748-A, Recorded April 16, 1919 (Courtesy

DAHR and Library of Congress)

General John J. Pershing

General Pershing was the U.S. Army general

who commanded the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in Europe during

World War I.

Years ago, when General Pershing,

then a handsome young Lieutenant with a slender waist and yellow

moustaches, was stationed as Commandant at the University of Nebraska,

Walter Scott was an officer in a company of cadets the Lieutenant

took about to military tournaments. The Pershing Rifles, they were

called, and they won prizes

wherever they went. After his graduation, Scott settled down to

running a hardware business in a thriving Nebraska town, and sold

gas ranges and garden hose for twenty years. About the time Pershing

was sent to the Mexican Border, Scott began to think there might

eventually be something in the wind, and that he would better get

into training. He went down to Texas with the National Guard. He

had come to France with the First Division, and had won his promotions

by solid, soldierly qualities. (p. 453)

General Pershing Decorating Officers

of 89th Div., Treves, Germany. Stereoview card 1918 (PM-1883)

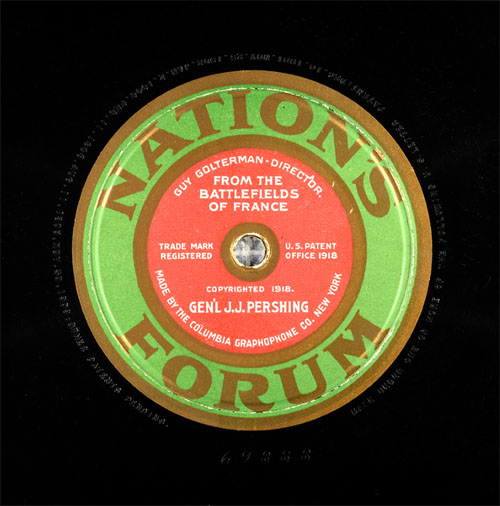

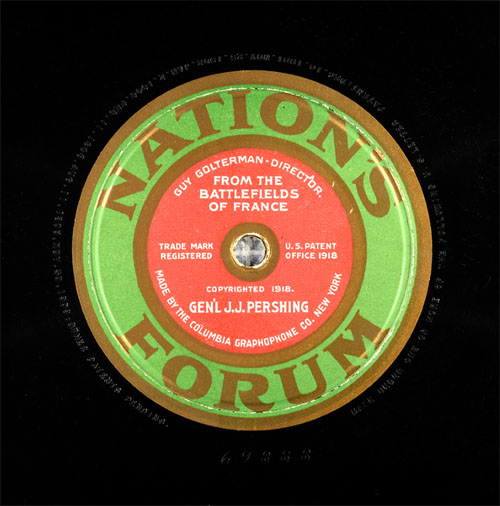

Hear the words from General John J.

Pershing "From

the Battlefields of France," The Columbia Graphophone Co.,

1918 (Courtesy of i78s.org)

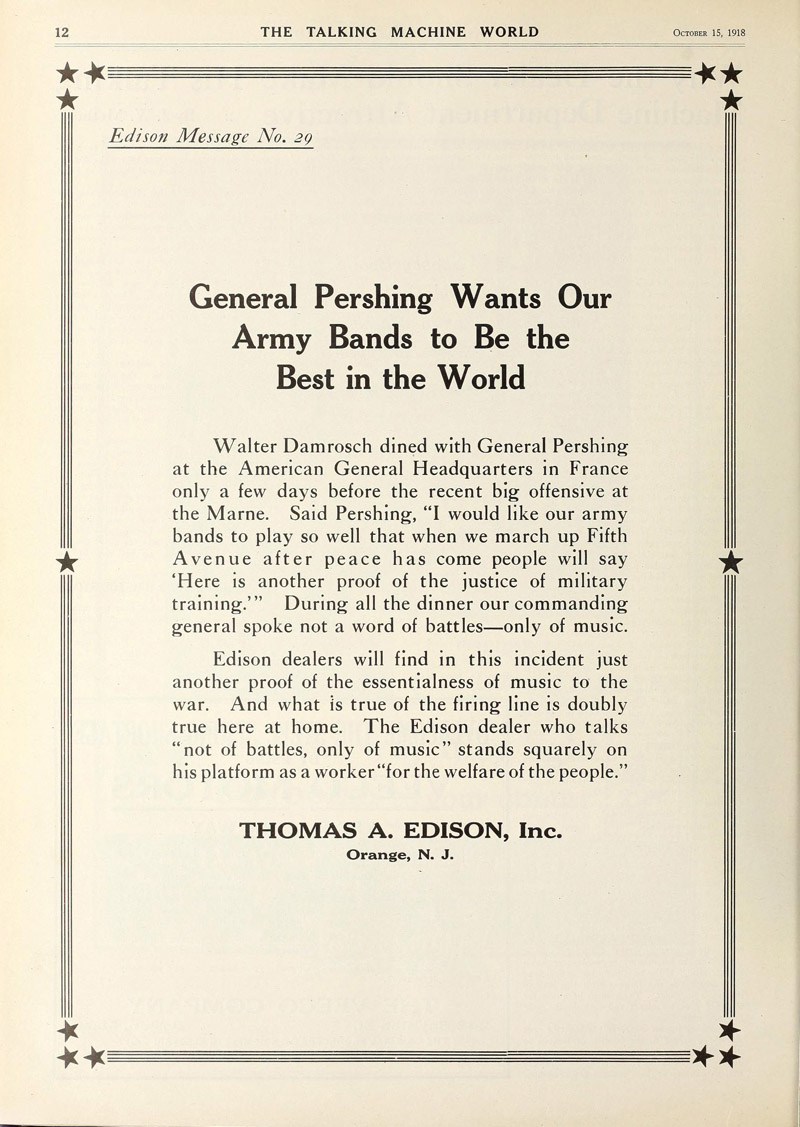

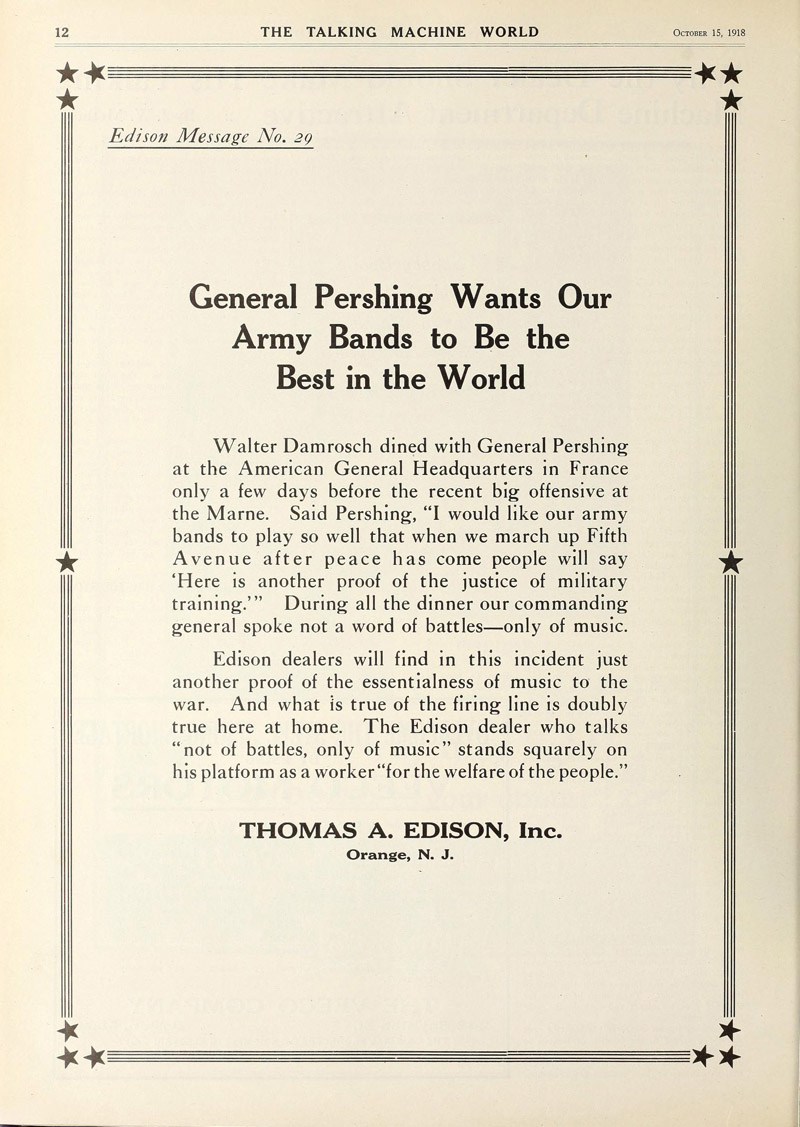

Edison Message No. 29,

The Talking Machine World, October 15, 1918

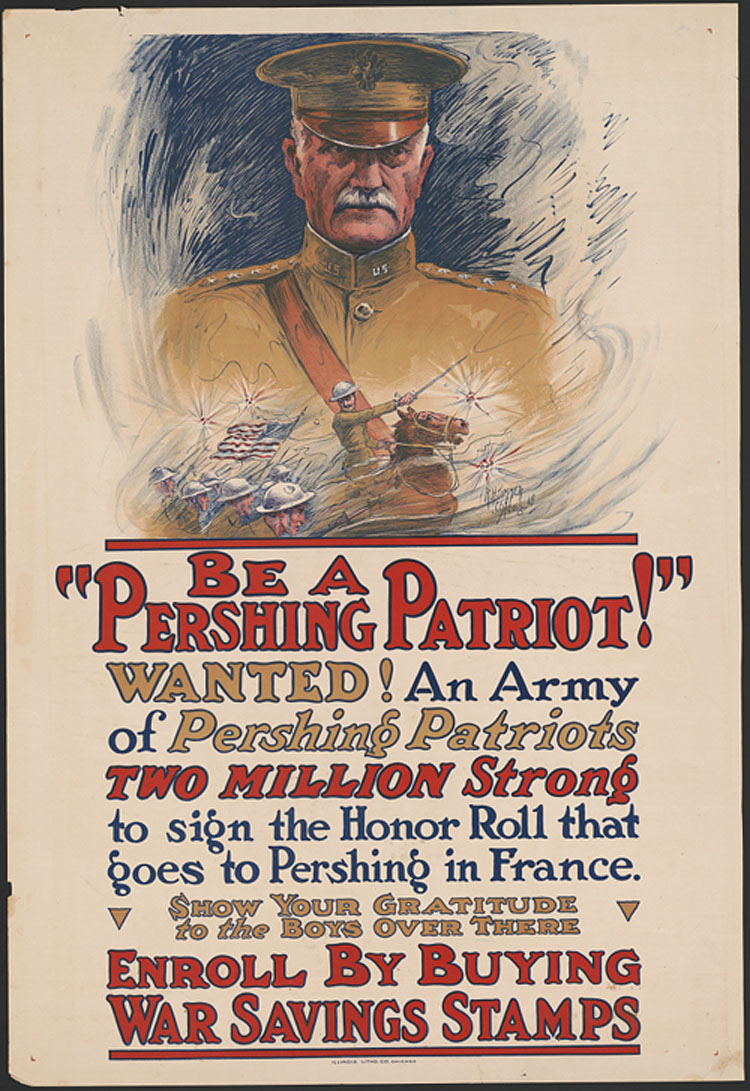

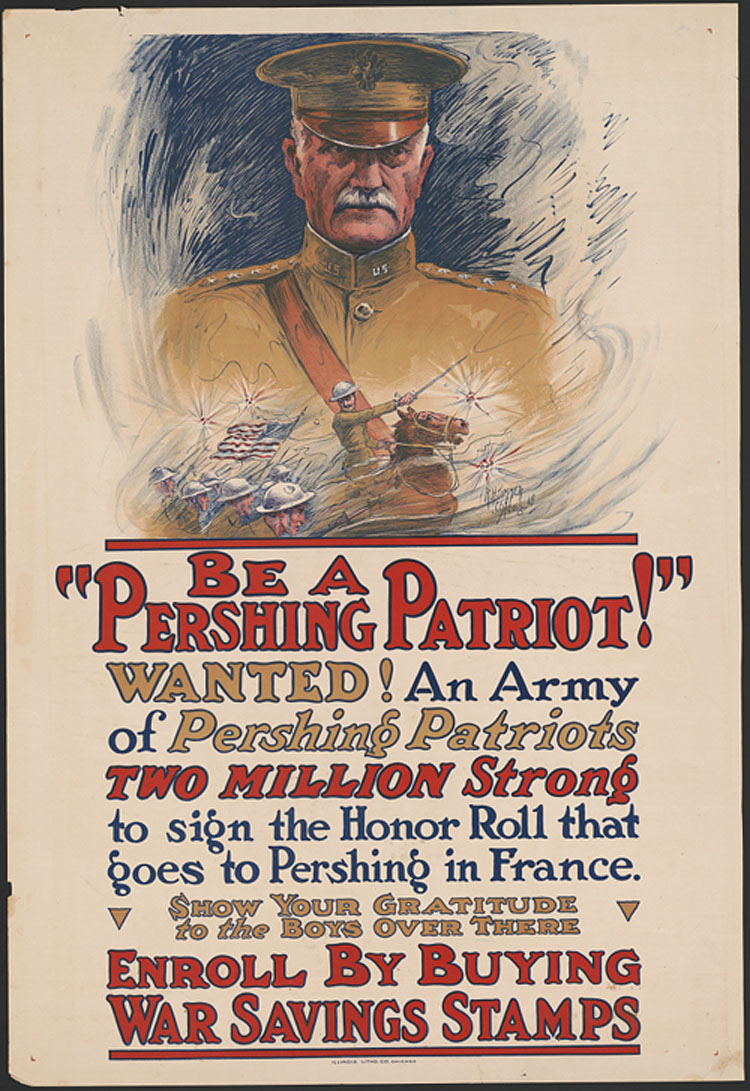

"A PERSHING PATRIOT!" Buy

War Savings Stamps, poster by R.H. Sommer, Illinois Litho. Co., 1918

(Library of

Congress)

British troops in World War I from "They

Shall Not Grow Old" by Peter Jackson (Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures,

©2018)

One of John Philip Sousa's fears in

his 1906 article "The Menace of Mechanical Music" was that

military music would be replaced by phonograph records:

Shall we not expect that when the

nation once more sounds its call to arms and the gallant regiment

marches forth, there will be no majestic drum major, no serried

ranks of sonorous trombones, no glittering array of brass, no rolling

of drums? In their stead will be a huge phonograph, mounted on a

100 H. P. automobile, grinding out "The Girl I left Behind Me,"

"Dixie," and "The Stars and Stripes Forever."

"The

Menace of Mechanical Music" by John

Philip Sousa, Appleton's

Magazine,

September 1906

"General

Pershing March" played by Victor Band, Record 18607-A, Recorded

on August 5, 1919 (Courtesy of

i78s.org)

Respectfully Dedicated

to General John J. Pershing

"Hats off to the Red White and

Blue," Words by Chester R. Hovery. Music by Ralph F. Beegan.

Publisher Jerome H. Remick & Co., Detroit, 1918 (Source: The

Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music)

In the Trenches and No Man's Land

FOUR o'clock . . . a summer dawn

. . . his first morning in the trenches. Claude had just been along

the line to see that the gun teams were in position. This hour,

when the light was changing, was a favourite time for attack. He

had come in late last night, and had everything to learn...

That dull stretch of grey and green

was No Man's Land. Those low, zigzag mounds, like giant molehills

protected by wire hurdles, were the Hun trenches; five or six lines

of them. He could easily follow the communication trenches without

a glass...

Their own trenches, from the other

side, must look quite as dead. Life was a secret, these days....

It all took place in utter darkness.

Just as B Company slid down an incline into the shallow rear trenches,

the country was lit for a moment by two star shells, there was a

rattling of machine guns, German Maxims,—a sporadic crackle that

was not followed up. Filing along the communication trenches, they

listened anxiously; artillery fire would have made it bad for the

other men who were marching to the rear. But nothing happened. They

had a quiet night, and this morning, here they were! (pp.478-479)

"The Rose of No Man's Land"

by Jack Caddigan and James A. Brennan. Published by Jack Mendelsohn

Music Co., Boston, 1918 (Courtesy

The

Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music)

"The

Rose of No Man's Land" by Moonlight Trio, Edison Domestic

Series 3677, 4-minute celluoid cylinder, recorded October 11, 1918

(Courtesy of i78s.org)

"The

Midnight Attack," Played by Prince's Band, Columbia Record

A1339, Recorded April 16, 1913 (Courtesy

Library of Congress)

"The Boys in Khaki

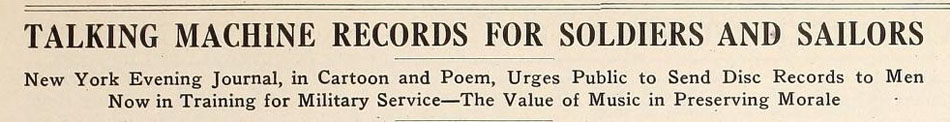

are in the Trenches," The Talking Machine World, July 1917

"Caruso is singing

in the trenches"

“Caruso is singing in the trenches

of France tonight…Thousands of miles from home in a land torn

by battle, our boys yet listen to the spiritual voice of Art. Through

the Victrola, the mightiest arts in all the world sing to them the

hymn of victory, cheer them with their wit and laughter, comfort and

inspire them.” Victrola ad, The Theatre Magazine, November

1918 (PM-1944)

Listen

to Enrico Caruso singing "Over There."

Listen

to Alma Gluck singing "Home, Sweet Home."

Listen

to John McCormack singing "Roses of Picardy."

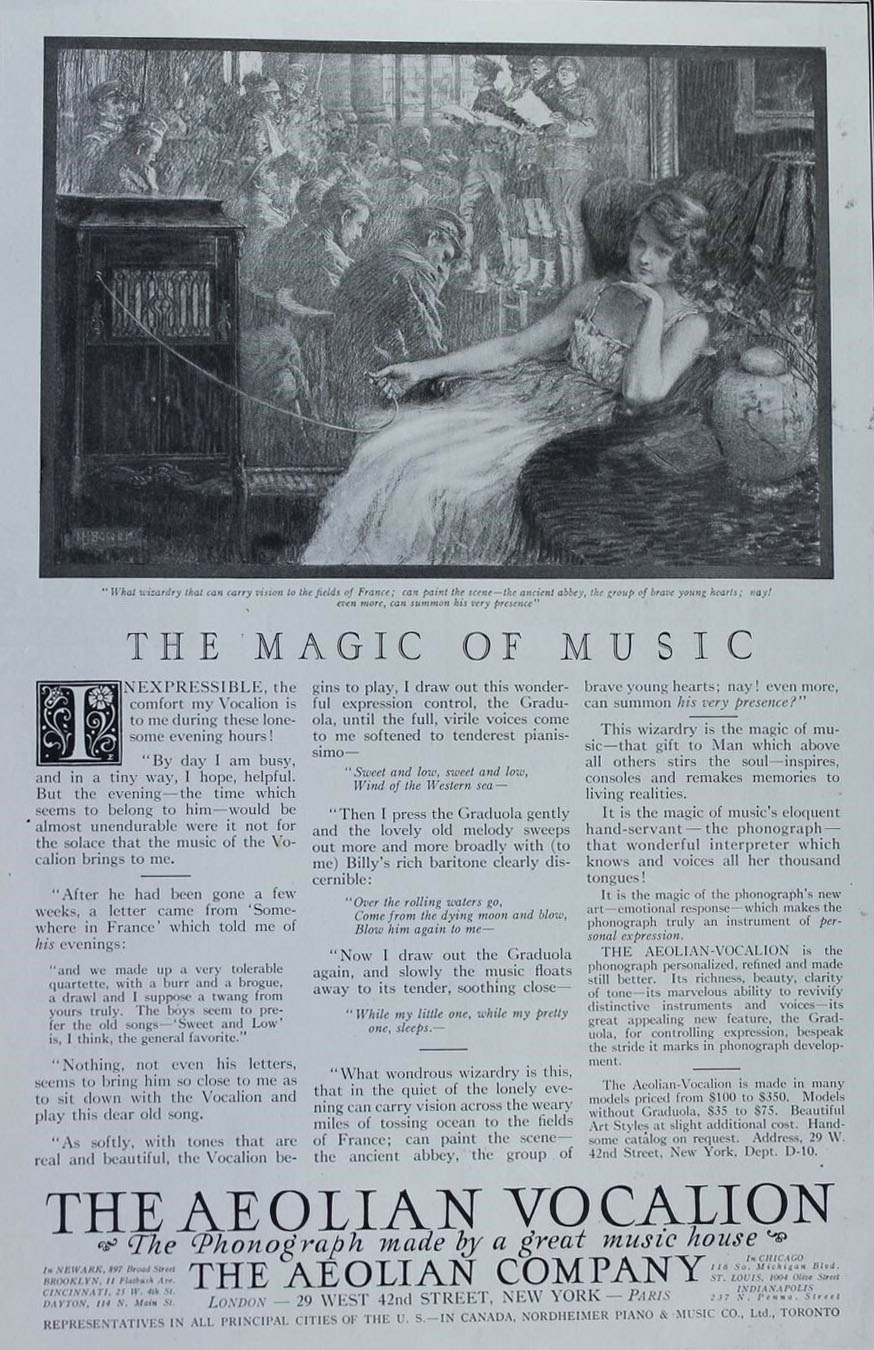

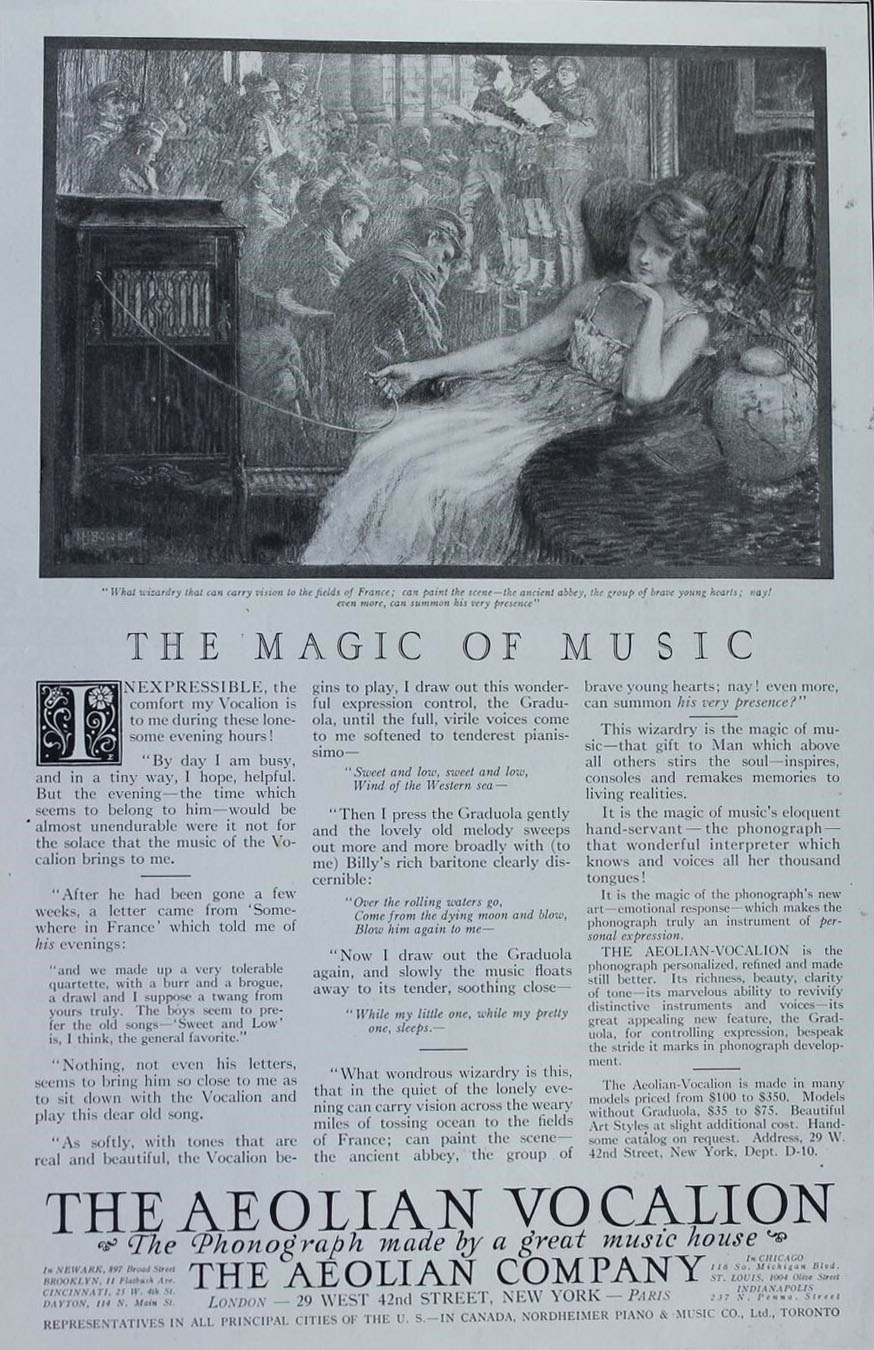

The Wizardry of the Aeolian-Vocalian

Phonograph can "summon his very presence" from the fields

of France, Aeolian-Vocalion 1917

Watch

Trailer for "They Shall Not Grow Old"

by Peter Jackson for a haunting time travel experience to World War

I (Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures, ©2018)

"His Master's

Voice" 12" 78 RPM record by the Gramophone Co., Ltd.,

1918

This record from ValueYourMusic

website was submitted by Allen Koenigsberg who also cautioned that

"there may be some controversy over the circumstances of this

recording."

The record is said to be the actual

recording of gas shell bombardment by the Royal Garrison Artillery,

9th October 1918, preparatory to the British Troops entering Lille

and "the only authentic sounds of the First World War."

"This record was made by

HMV’s top Recording Engineer, Will Gaisberg, outside Lille in France

on 9th October 1918 and rushed back to England for issue, but by

the time it saw release the Armistice had been signed and, consequently,

sales were very poor." (ValueYourMusic.)

According to The

Church of the Epiphany, "by the time the recording was

completed, the war was over. Gaisberg had been slightly gassed during

the expedition, and fell victim to the flu pandemic and tragically

died a month later" on 5 November 1918.

Aeroplanes and Victor Morse

Claude said he had a friend in the

air service up there; did they happen to know anything about Victor

Morse?

Morse, the American ace? Hadn't

he heard? Why, that got into the London papers. Morse was shot down

inside the Hun line three weeks ago. It was a brilliant affair.

He was chased by eight Boche planes, brought down three of them,

put the rest to flight, and was making for base, when they turned

and got him. His machine came down in flames and he jumped, fell

a thousand feet or more.

"Then I suppose he never got his

leave?" Claude asked.

They didn't know. He got a fine

citation. (p. 493)

French Fliers Ready

for Action On the Battle Line. Stereoview card 1918 (PM-1892)

A multiple-degrees of separation connection

with the phonograph and air service personnel in the US military is

made with Scientific American's February 20, 1915 cover illustration

and story "The Phonograph Leaves the Air Scout's Hands Unhampered."

A phonograph is pictured with the observer in the aeroplane looking

through his binoculars with one hand while the other hand is writing

down information and the phonograph ready for dictation.

The Phonograph Aids

the Aeroplane Air Scouts, Scientific American (PM-2064)

The article inside, titled "Mechanical

Aids for Air Scouts," explains "in carrying out scouting

observations with military aeroplanes it is essential that there be

two men in the machine, namely, a pilot whose sole duty it is to operate

and steer the craft, and an observer who can devote undivided attention

to scanning the ground below him and making sketches of fortified

works, the disposition of the enemy's guns, the movements of their

troops, and the like...If the observer is to make sketches of the

ground over which he is flying, he will be some much occupied, probably,

as to not to have time to jot down notes...a phonograph is now provided,

with a speaking tube running to the observer's mouth, so that he may

talk into the machine at any time during the flight and thus make

a record of his observations..."

Scientific American

(PM-2064)

Support for the Troops

"In camp or trench, on transport

or battleship, in hospital, church and cantonment...the Victrola is

enlisted in the War for Democracy." "Every Victrola in the

service of Uncle Sam is a source of actual war strength." Victrola

Ad, The Talking Machine World, July 15, 1918

“A Church Service On The Battlefield"

Russell Hunting performed this descriptive

record for Pathé Frères Phonograph Co. of a church service

for United Kingdom troops on the battlefield with Rock of Ages,

a prayer and then a bugle call in response to an imminent attack.

"A

Church Service On the Battlefield," Pathé Record 35067

is Side B of "The Battle of the Marne," 1917 (Courtesy of

i78s.org)

Record Bulletins for

January 1918

The Talking Machine World,

December 1917 Pathe Record (Composer is John Greenleaf Whittier)

The Talking Machine

World, January 15, 1918

The Talking Machine

World, January 15, 1918

The Talking Machine

World, January 15, 1918

"They All Sang Annie Laurie,"

Words by J. Will Callahan, Music by F. Henri Klickmann, Publisher

Frank K. Root & Co., New York, 1915

The Talking Machine

World, March 15, 1918

"Victrolas and Victor Records are

day and night advancing the cause of freedom on the battlefields of

the entire world...Every Victor Record at the front is a winged messenger

of victory..."

The Talking Machine

World, July 15, 1918

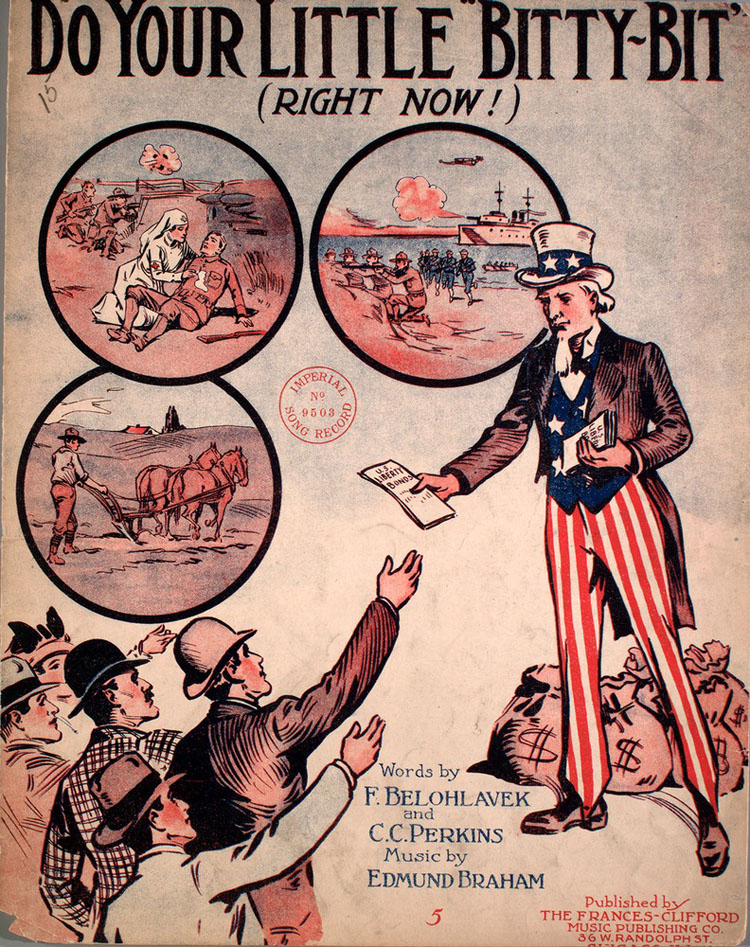

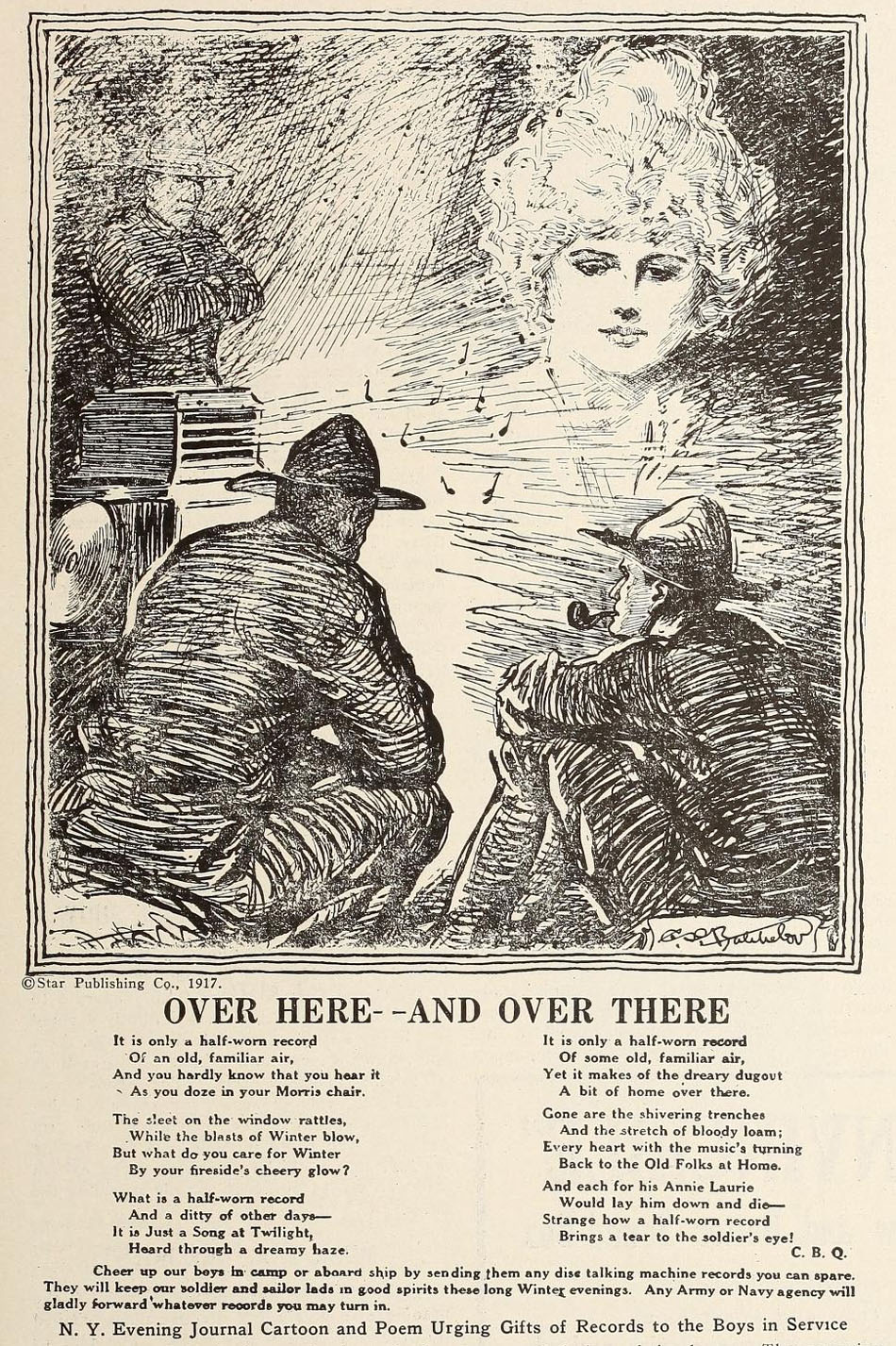

"Do Your Little "Bitty

Bit" (Right Now!)" by F. Belohlavek and C.C. Perkins.

Music by Edmund Braham. The Frances-Clifford Music Publishing

Co., Chicago, 1917. (Source: The

Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music)

LISTEN:

Do Your Little "Bitty Bit," by Joe Remington, Pathe

Freres 78rpm Record No, 20422, 1918 (Source: Internet Archive).

Soldier's bayonet used as needle to

play message on the record: "It says the folks at home hav'nt

forgotten us."

When I Hear

That Phonograph Play, M.

Witmark & Sons, New York 1918

James Francis

Driscoll collection

of American sheet music

Making a record as

a message to you who will remain, French newspaper, 1916 (PM-2080)

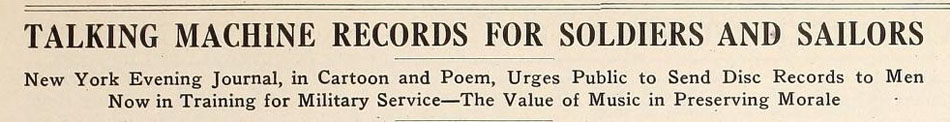

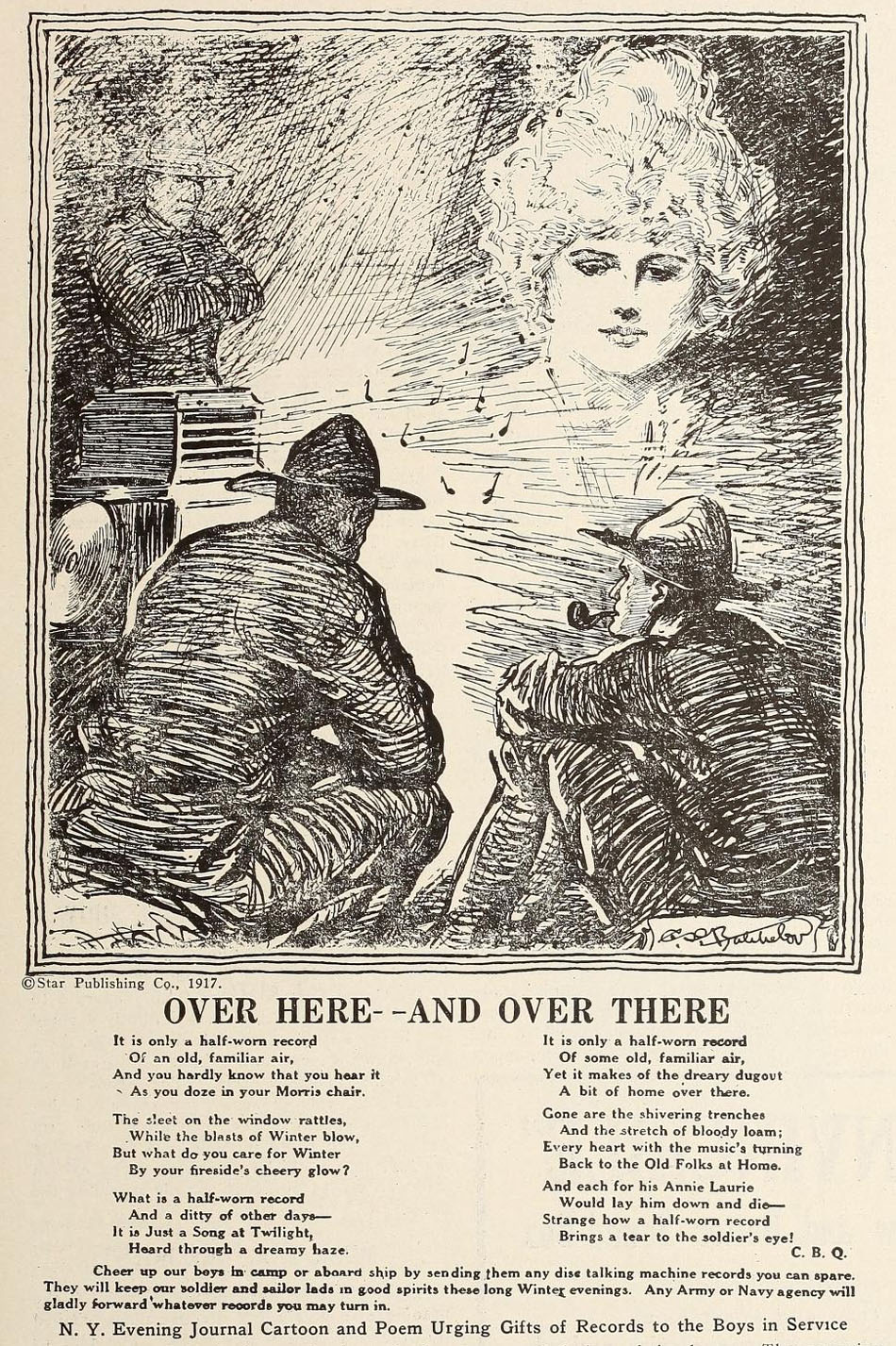

"The talking machine is undoubtedly

the greatest comfort to the men in the camps, as it is to the men

in the trenches at the front." (7B)

The Talking Machine

World, January 15, 1918

Note the following sheet music and

the contrasting American opinions exemplified by the American anti-war

song of 1915 "I Didn't Raise My Boy to be a Soldier" to

this 1918 "I'm Glad to be the Mother of a Soldier Boy."

This morphying was suggested to me by Allen Koenigsberg with

his example of the 1917 song "I'm glad I raised my boy to be

a soldier!" (poem and copyright by Wm. F.J. Smith ; music by

R.A. Browne, 1917, monographic,

(Library of Congress).

"I'm Glad to be the Mother of a

Soldier Boy," by Bronner and Bowers, Frederick V. Bowers, Inc.

Music Publishers, New York, 1918. (Courtesy

The

Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, The Sheridan Libraries,

Johns Hopkins University).

The Bugle

In the First World War "the introduction

of telegraphs, field telephones and wireless" resulted in the

bugle being used less for communicating field instructions than in

previous wars (see below for an example of a World War I "trench"

bugle which also speaks for itself how different this war was in defining

the battlefield). Bugle calls, of course, were part of daily military

life in camps (e.g., Reveille, Assembly, Mess calls, Recall, Taps)

and for ceremonies such as funerals. (8)

All the garden flowers and bead

wreaths in Beaufort had been carried out and put on the American

graves. When the squad fired over them and the bugle sounded, the

girls and their mothers wept. Poor Willy Katz, for instance, could

never have had such a funeral in South Omaha. (p. 574)

The World War One 'descriptive' record

“A Church Service On The

Battlefield" by Russell Hunting included a bugle call in

response to an imminent attack.

Sheet music by Irving Berlin, published

by Waterson, Berlin & Snyder, New York (1918). Courtesy Music Division,

The New York Public Library

LISTEN

to "Oh! How I Hate to get up in the morning" by Arthur

Fields, Edison 4-minute celluloid cylinder, Record No. 3639, recorded

July 16, 1918 (Courtesy i78s.org)

G. P. Cather, the prototype for Claude

Wheeler, played the bugle and his family donated G.P.'s bugle to the

Willa Cather Foundation. The Collection's on-line

information about G.P. Cather's bugle includes the following:

J.W. Pepper brass bugle, circa 1904.

Grosvenor P. Cather performed with several bands during his time at

Grand Island College, and he was the bugler of the College Cadets

drill team. The bugle, though showing its age, was a cherished Cather

family heirloom. A crude “C” can be seen in the brass near the mouthpiece."

"G. P.'s family was under the

impression he took the bugle to Texas on the Mexican Expedition."

(9)

Credits: OBJ-335-001. Charlotte Shaw

and Kenneth Smith Collection. Willa Cather Foundation Collections

and Archives at the National Willa Cather Center in Red Cloud, NE.

This brass military bugle (below) is

from the Minnesota

Historical Society and is an example of the M1894 bugle in B flat,

or "Trench" bugle used during World War I. (10)

There are a number of phonograph records

made demonstrating military bugle calls or with the bugle call as

part of a descriptive record or song.

U.S.

Army bugle calls (No. 1) by S. W. Smith (U.S.N.) & Bugle Squad,

Edison 4-minute celluloid cylinder No. 3331, recorded August 1, 1917

(Courtesy i78s.org)

U.S.

Army bugle calls (No. 2) by S. W. Smith (U.S.N.) & Bugle Squad,

Edison 4-minute celluloid cylinder No. 3332, recorded August 1, 1917

(Courtesy i78s.org)

f f

A

Soldier's Day (The Way Army Bugle Calls Sound To the Boys) by

Geoffrey O'Hara, Victor 10" double-sided disc, Date

April 18, 1918, Record No. 18451 (Courtesy i78s.org)

Home, Sweet Home

When they walked back across the

square, over the crackling leaves, the dance was breaking up. Oscar

was playing "Home, Sweet Home," for the last waltz. " (p. 580)

"Home

Sweet Home" sung by Alma Gluck, Victor Red Seal 74251,

1911 (Courtesy of i78s.org)

"Home, Sweet Home,"

on the Gramophone. Postcard 1906 (PM-0669)

"Home,

Sweet Home The World Over," November 1912 Edison Phonograph

Monthly, 4-minute Edison Blue Amberol Record No. 1600 (Courtesy

i78s.org)

This pre-war recording of "Home,

Sweet Home" includes Germany, soon to be in conflict with the

other Home, Sweet Home examples on this record (e.g., Spain,