By Doug Boilesen 2023

Demonstrations of the phonograph and

its recorded sounds have attracted attention, entertained, and been

used to sell phonographs and records throughout the phonograph's history.

There have been different devices, records and venues for these demonstrations

but the phonograph industry has always found ways for the public hear

it for themselves.

In the beginning Edison's tinfoil Phonograph

demonstrations featured a machine that was seen as a novelty which

could magically capture and replay sound - a voice, a trumpet, a dog

barking. It was also promoted as the new scientific wonder made by

"The Wizard of Menlo Park," sometimes referred to in newspapers

as Professor Edison."

While the early demonstrations might

have had similiarities with going to a carnival sideshow, a magic

show or a science lecture, a decade later the improved phonograph

had a new public venue with its introduction as a coin-in-the-slot

entertainer. It was a profitable business, so much so that it was

soon followed by machines and respective advertising designed to bring

the phonograph into the home and a much larger market.

To make it a popular home entertainment

device the phonograph industry had to keep improving its sound quality,

make it cheaper and offer a variety of more and more records. Regarding

the listening quality some early 20th century advertisements confidently

stated that there was now no difference between live performers and

recorded voices. The public was accordingly asked again to hear it

for themselves but now there were local phonograph dealers available

to provide those demonstrations.

Acoustic recordings would be replaced

by electric recordings in the 1920's and 1950's advertisements promoted

high-fidelity followed by stereophonic sound. Each change was accompanied

with the proposition that the quality of sound could be verified with

demonstrations and "if you hear it you'll want it."

The following is a gallery with examples

of how the phonograph has been demonstrated ever since its first public

words were heard in the offices of Scientific American on December

7, 1877. From then on the phonograph industry has said it wanted the

public to hear it for themselves. As one of the phonograph's advertising

phrases succinctly put it "Hearing

is Believing!"

Demonstrating the

Phonograph - 1878

Early tinfoil phonographs were exhibited

in meeting halls, opera houses or wherever a lecture/demonstration

could be held. For 25 cents you could hear "The Greatest Triumph

Known to Ancient or Modern Science!" (4A).

Those demonstrations could include some facts from a science and technology

perspective but most were attending for the experience of hearing

for themselves the "wonder" of a machine that records and

reproduces voices and sounds.

Curiosity and the novelty of such a

device were the early incentives to pay money for a presentation.

It's easy to think of those early tinfoil phonograph demonstrations

as sideshow attractions since the public's expectations weres defined

in a "come and hear it for yourself" style promotions. It

was a chance to see an actual recording made and hear a machine repeat

back whatever had been recorded. With the turn of a crank the Phonograph

magically performed: "It Talks! It Sings! It Laughs! It Plays

Cornet Songs."

Listeners were surely astonished at

what they heard from the simple device. There were also a few skeptics

who thought there must be a ventriloquist

or some trick taking place -- understandable reactions since the demonstration

of such a device had those elements of a magic show -- but there was

no rabbit being pulled from a hat and no ventriloquist.

The writer of the Scientific American

article describing what was witnessed at the Phonograph's first public

demonstration summarizes the experience that many must have felt:

"It is impossible to listen to the mechanical speech without his experiencing

the idea that his senses are deceiving him." Scientific

American, December 22, 1878.

The recording medium of Edison's Phonograph

was originally tinfoil so the process of recording sound could be

demonstrated but the 'recording' itself could not be removed and replayed.

Pieces of the tinfoil, however, did make nice souvenirs for the paid

patrons of these exhibitions. Those demonstrations were not promoting

a consumer product, but they were offering the experience of seeing

a recording of the human voice being made and then witnessing, with

their own ears, the replay of the recorded sound in what was essentially

a one-time listening performance.

The Laramie Daily

Sentinel, May 3, 1878

A little more than a decade after Edison

demonstrated his tinfoil phonograph to President Hayes in the White

House Edison's "Perfected" Phonographs and Columbia Graphophones

were playing wax cylinder records. Those new listening devices would

again be limited by location and number of machines available but

the phonograph's record now had a longer life-cycle which allowed

it to be played multiple times.

Nickel-in-the-Slot Phonographs -

1889

The phonograph's business case also

would improve with the introduction of the new coin-in-the-slot phonographs

which proved to be popular and profitable. Records of the early 1890's

featured band music, quartettes, vocal and cornet solos and talking

monologues which could be humorous, risque, a story, or perhaps even

an advertisement for soap followed by some free band music.

The first nickel-in-the-slot phonograph

was installed by Louis Glass inside the Palais Royale Saloon in San

Francisco on November 23, 1889. In a sense, this was the official

audition of the new and personal way to hear music and recorded stories

which were not dependent on a traveling exhibitor demonstrating the

phonograph or a live performer in a music hall.

Patrons could read the name of the

record on the machine's sign board and follow its directions; or the

proprietor or phonograph parlor attendant could provide assistance.

There was only one record per machine but it gave many people their

first experience of recorded sound and potentially the interest to

hear another story or song.

Albert K. Keller nickel-in-the-slot

phonograph, Electrical Review, August 9, 1890 (Courtesy Allen

Koenigsberg)

.

While coin-in-the slot machines were

appearing in saloons, hotels, ferry depots, and other public locations

traveling phonograph exhibitors and salesmen were also providing phonograph

concerts and demonstrations in towns of all sizes.

The Red Cloud Chief,

Red Cloud, NE, August 28, 1891

Phonograph Rooms and Phonograph Concerts

- The 1890's

In Kalamazoo, Michigan's "the

first "Phonograph Rooms” were opened in 1895 at the northwest

corner of West Main and Rose streets in the Chase Block, where locals

were given the chance to “investigate phonographs and graphophones

for family use” (The Kalamazoo Gazette). Although the business only

lasted a short time, it did help introduce the locals to the idea

of recorded music. ("Kalamazoo’s Early Music Stores,"

Kalamazoo's

Public Library, December 6, 2023). By

1915 many of the larger stores had listening

rooms, demonstration booths and even "recital halls"

to provide listening environments designed to provide the best listening

experience and encourage sales.

There are also many examples of phonograph

'concerts' in small towns across the country where the phonograph

was being exhibited at a school, or used for fund raising, or part

of a social gathering at someone's home where the phonograph might

have been purchased and been the only one in town.

Sociable at the residence

of Mrs. A. H. Brown with supper and one selection on a phonograph

free. The Red Cloud Chief, Red Cloud, NE, November 17, 1893,

"The Graphophone

Social," The Phonoscope, November 1898

Graphophone concert to

raise money for a public school flag, The Phonoscope, November

1898

Phonograph music could also be combined

with a magic lantern show, a moving picture show, illustrated song

slides, or with a local live performance at a church, school, or local

opera house.

It was cautioned by some, however, that

if phonograph dealers weren't involved in some way with these performances,

the "demonstrations" of the phonograph could result in negative

opinions about phonograph records. In 1910 one dealer commented in

The Talking Machine World exactly to that point, saying the

tendency to stop using phonograph records for the song slides at the

movies and replace them with live singers was a good thing. Why? Because

the records were being played so much they could hardly be understood

and "the result was anything but good publicity for the talking

machine."

The Talking Machine

World, September 1910

See the gallery of

Magic Lantern Shows for some re-created examples which use magic

lantern slides accompanied by cylinder phonograph records to illustrate

how the Phonograph and the magic lantern could provide multimedia

entertainment to paying audiences circa 1900.

See the gallery of Phonograph

Music for the Movies for examples of phonograph music used in

local movie houses to demonstrate the phonograph and provide music

for the 'silent movies."

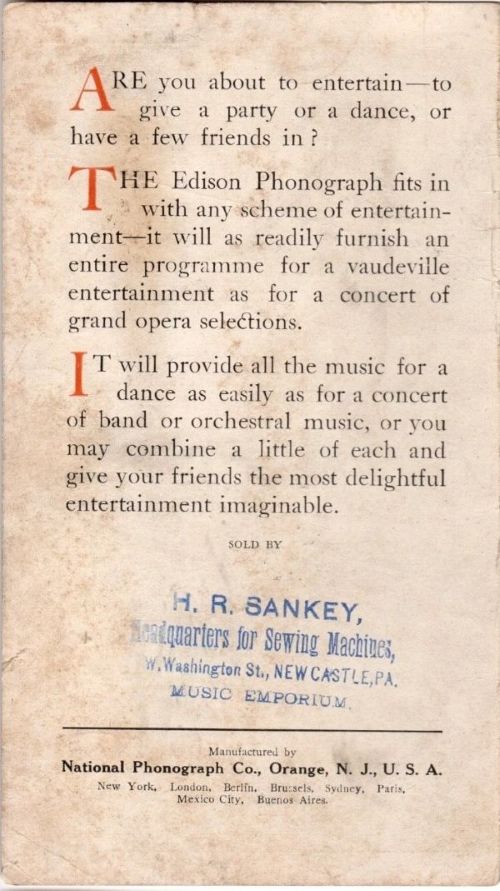

The Edison concert phonograph

- "Have you heard it?" c.1899 [Cincinnati ; N.Y.: The U.S.

Printing Co] Photograph.

Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

"Half

the Pleasures in Life come through the ear. The only way

to preserve these pleasures in their perfection, and enjoy them at

will is by owning a genuine Edison Phonograph."

Munsey's Magazine,

February 1899, 2 3/4" x 4"

A phonograph concert was also a way

to normalize the phonograph, a machine, as being the performer

in a music program and an entertaining substitute for live performers.

An 1896 Berliner Gramophone Christmas ad in Munsey's Magazine featured

an attentive and smiling group in a private parlor listening to a

home entertainment "Programme." The 'playlist' was

included as part of the ad with this being one of the earliest phonograph

"playlists."

Munsey's Magazine,

December, 1896 (PM-0910)

The Outlook, November

28, 1896 (back cover) - Note: Earliest known version of this ad was

published in The Christian Work, November 19, 1896 p. 822.

(Courtesy Allen Koenigsberg). See

Phonographia's 1896 Berliner

Gramophone Christmas Programme to listen to records from this

playlist.

The 1900's

Phonograph dealers continued sponsoring

concerts and public demonstrations, often presenting them as a free

"Grand Concert" for the general public.

The following is an example from 1905

of the Thomas Book Store, which sold Edison Phonographs and Records

in Madison, Nebraska, renting the local Hein Opera House to put on

a free phonograph concert. The event was noted in the November 1905

edition of The Edison Phonograph Monthly.

A merchant in Ponca City,

Oklahoma in 1905 gave a phonograph demonstration in Koller's hardware

store to rave reviews according to the Edison Phonograph Monthly.

"Finest instrument we ever saw or heard..." "Entertainment

was better than most fifty cent shows."

The Edison Phonograph

Monthly, May 1905

Edison Pamphlet - Grand Konzert Today Admission 2 Marbles (PM-2279)

Inside Edison Pamphlet (PM-2279)

Backside of Edison Pamphlet (PM-2279)

Come hear the

phonograph for yourself.

"Hearing is Believing

-- and you can hear today at the nearest Columbia dealer's."

"It is reality, nothing less;

for "The Stage of the World" presents the artists

themselves to you..." Columbia Grafonola, 1916

"You Can Afford

the Best But You Cannot Afford to Buy a Phonograph Before Hearing

The Pathé Pathéphone." The Talking Machine

World, June 15, 1915

Edison Tone Tests

1915 - 1925

Edison conducted Tone Test ‘recitals’

from 1915 to 1925 to demonstrate his new Diamond Disc phonograph

recordings. Those demonstrations weren't simply to listen to a

record. Instead, listeners

would be asked if they could distinguish between a live performing

artist and an Edison record.

The Literary Digest

for January 24, 1920

"After you have

heard the New Edison you could scracely be contented with a talking

machine. In your locality there is a merchant licensed by Mr.

Edison to demonstrate this new instrument. You will not be importuned

to buy." - "The Test of Tests," The

Saturday Evening Post, 1917.

For more details about

the Edison Tone Tests see Phonographia's Edison

Tone Tests.

Demonstration

Records - 1950's and beyond

The demonstration of records

continued as new record formats and devices were introduced. One way

of promoting the introduction of the long-playing 33 1/3 records in

the 1950's was by creating "demonstration Records" which

were designed to impress listeners with the quality of the recording

and the improved performance of a high-fidelity phonograph.

When stereophonic sound

was added to phonograph records there were again 'demonstration records'

to showcase what the new dimension of stereo brought into the home.

Trade magazines like Stereo Review and Ohm Acoustics, a maker

of stereo speakers, and others would also create demonstration records

to support the proposition that what was being heard with each new

demonstration record was the new state-of-the-art phonograph and its

records.

In 1954 RCA Victor issued

their demonstration LP record titled "Hearing is Believing"

and asked listeners to hear for themselves what "High Fidelity"

and the "brilliant RCA Victor New Orthophonic Recording"

could produce in a before and after listening test. RCA was

also introducing their new "Gruve/Gard" with its new raised

rim and center to "give permanent protection to the record surface."

"Hearing is Believing,

RCA Victor "New Orthophonic" Recording, The Saturday

Evening Post, October 9, 1954. (PM-1522)

"Hi-Fi Demonstration

Record - a musical test of phonograph performance," Capitol

Records, 1956 - A Demonstration Record Not for Sale

"with musical excerpts specially selected to help you judge

phonograph quality" and recorded in FDS - Full Dimensional

Sound.

Roulette Presents

A Demonstration of the New Dimensional Sound of Dynamic Stereo,

Roulette Records, Inc., 1958

"This recording

has been produced to introduce and demonstrate to the listener...DYNAMIC

STEREO."

"Stereo Review's

Stereo Demonstration Record - A stunning series of demonstrations

each designed to show off one or more aspects of music sound and its

stereo reproduction." Stereo Review's compilation record,

ZD-767, 1973. Pressed by Allentown Record, Co. - Ziff-Davies Publishing

Company, New York, N.Y.

Stereo Imaging Demonstration

Record, Ohm Acoustics Corp., Ultra-Analog Processing, 1982 (FP-1342)

"Stereo Imaging

is purely, but not so simply, the ability of loudspeakers to reproduce

music three-dimensionally. Most speakers can't....The cuts we've compiled

for this album will enable you to test your speakers for all three

of the elements comprising a stereo image: placement, height and depth,

and room ambience." (Back of album's explanation by Ohm Acoustics).

Record

Listening Booths in the 20th Century

Private listening booths

and demonstration rooms were designed to enhance the customer's listening

experience when shopping for a new machine or record. As such they

were another venue for the demonstration of recorded sounds.

For examples of listening

booths in phonograph dealer's stores, record stores, department stores,

libraries and popular culture, see Phonographia's Record

Listening Booths.

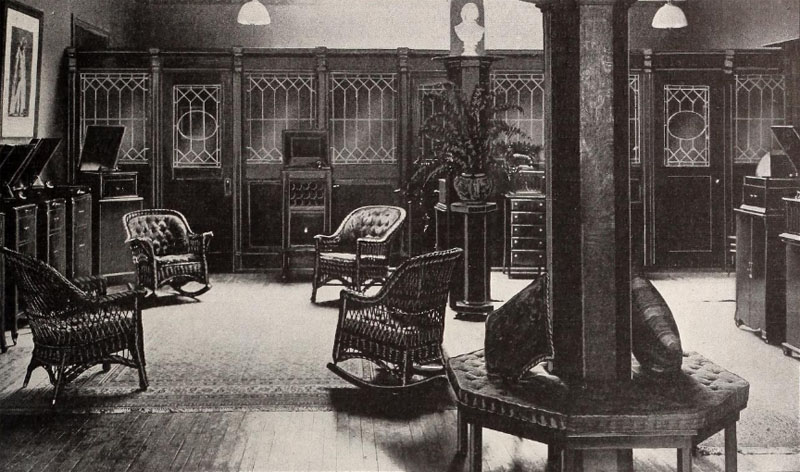

Installation for Fulton

Music Company, Waterbury, Conn. - The Talking Machine World,

May 1915.

Record Listening Room,

The Saturday Evening Post, April 19, 1952

Demonstration

Rooms in the 21st Century

Box stores like Best

Buy and audio stores specializing in higher-end sound systems

continue to offer customers the opportunity to listen to records and

digital recordings in their audio rooms where different speakers and

components can be switched back and forth. The listener of these demonstrations

is still being given the opportunity to find the right system per

their ears (and now also their eyes for the multimedia systems) and

their budget.

Demonstrations of sound

started with the tinfoil phonograph demonstrations and ever since

there have been "hearing is believing"; experiences. The

major difference, however, is that for most it's no longer a wonder

to experience ephemeral sound captured and heard. Instead, the

demonstrations in stores is connected with whether or not what you

hear is worth purchasing, i.e., is it significantly better than how

you already experience sound; is there some new benefit to how you

can hear music if you purchase a new music delivering device; or does

streaming of music and the wireless headphones/earbuds make those

decisions even simpler?

The technologies and quality

of sound and variety of music available have exponentially changed.

Physical media and phonograph records are niche formats. The shift

to more personal listening also is a factor. Fundamentally, however,

whether it's a family listening to music as part of a home entertainment

system or a single listener streaming music from their iPhone, the

"Stage

of the World" and "Best Seat in the House" advertising

messages have not changed: You, as the listener, are still being offered

the best seat in the house.

For myself, however, having

the best seat in the house for listening to the recorded music of

world, anytime, anywhere

and as often as I want will always be associated with the wonder and

magic of the phonograph and recorded sound.

Perhaps that's because

I'm a Friend of the Phonograph.

But I think it's more than

that, and would suggest that the Scientific American writer's

reaction at the phonograph's first public demonstration is a reminder

of that wonder and magic when he wrote "it is impossible to listen

to the mechanical speech without his experiencing the idea that his

senses are deceiving him."

It was a wonder in 1877.

It's still a wonder today.