|

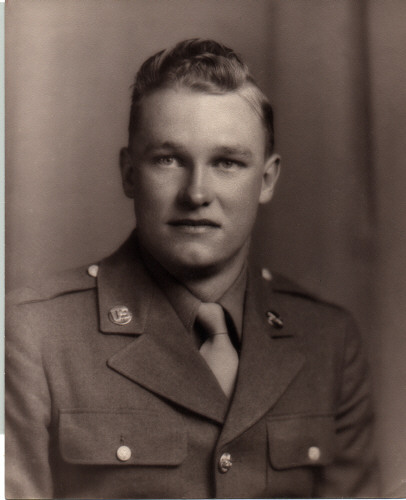

Axel Boilesen and World

War II

By Axel Boilesen, December 1996

Several months ago while visiting at

our friend Dorothy McVicker's home she and Betty suggested that I

write a brief account about my military service. This is an attempt

to fulfill that request.

I have avoided thinking about or talking

about that 2 years, 3 1/2 month period of my life largely because

of its lack of realism, its lack of clarity in some respects, and

ultra-clear memories and emotions in other respects.

At the time of my entry in the military

I had an agricultural deferment to operate the farm. I do not remember

the decision making process connected with the deferment - -but I'm

certain it was never discussed. All I do remember is one morrning

when finishing the milking I turned to my Dad and said "I want

to join the Army" to which he replied "Son, I am not surprised.

When would you like to sign up?" I told him "today would

be fine."

Pop, Axel and Mom

When I look back at it 50 years later

the briefness of that decision and the lack of my mother's involvment

is strange. She had the most to lose by my going to war but I had

no thought but that she would support my decision.

Axel holding nephew

and niece Russell and Leila Stevens on the Sunday before going into

the Army.

Camp Roberts, California

My military dream was to fly a P-38

which occasionally we would see fly over and so when I volunteered

I indicated a preference for the Army Air Corp. Upon taking my physical

I was told my depth of perception eye test would not allow me to ever

be a pilot and I was sent to basic training at Camp Roberts, California

in the Field Artillery branch of the Army.

As I reflect back this was a big change

for someone who had been spending 10 hours a day doing field work

and essentially isolated a majority of the time.

Two examples illustrate the change.

First, at the induction station at Fort Crook on that first night,

cots were set up for hundreds of recruits in one large room. At the

time of lights out we were told in very descriptive language who we

were, our family lineage and a few threats if we did not follow orders.

It was not a "Good night, John-Boy" closing for the day.

The second example was more shocking and was a regular pay-day ritual.

Imagine the requirement for all to assemble totally buck naked in

one large room and pass the medical review team one by one (apparently

for the purpose of checking for venereal disease.) The saying as I

remember it was "Eyes right, foreskins tight and assholes to

the rear."

The change in privacy was never questioned

but did require adjustments. Regarding basic training, in retrospect,

I have very positive feelings. When inducted my weight was listed

at 150 pounds and height 6' 0". At Camp Roberts the barracks

were single story frame structures each housing 50 to 60 men. We had

single bunk beds and a foot locker at the toe of the bed. Inspections

were scheduled and unscheduled and we soon learned that demerits were

a common occurrence, but generally reasonable.

A Sergent Thompson, from the midwest,

was our platoon leader and was a gentleman I respected. Looking back

I must have been more quiet and reticent than the average because

I do not recall close friendships or bonds in basic training, or for

that matter all through my military service. Sure, I had a lot of

temporary friends that I liked to be with, but realizing I was in

a replacement category much of my military service, unconsciously,

I believe, I avoided developing really close friendships. Who knows,

it may have been for the best in the prevention of heartaches later

on.

Basic Training, Field Artillery

Back to basic training - the physical

training was demanding but I was used to hard work and kept up quite

well except for some of the calisthenics, wall climbing and gymnastic

skills. The forced marches, river runs and endurance tests were activities

that I could feel improvement in week by week.

The artillery training was with 105mm

howitzers and the commands proceeded as follows: Battery adjust (which

was to get at your position); Shell H.E. (which was of the high explosive

type, other types of shells included incendiary or smoke shells);

Charge 5 (which indictated the number of packets of powder in bags);

Fuse quick (or it may be a delay fuse or other time setting); Based

Deflection "X" degrees right or left (which was a reference

to the back setting of the range pole set up in the original alignment);

Up or Down "X" degrees (which was reference to the level

setting on the howitzer instrument mechanism); Followed by the command

to fire one round or more. At each command a crew member had specific

responsibilities regarding the preparation and loading of the shell,

inserting the powder, closing the breach block, adjusting the alignment

and elevation of the barrel and finally the pulling of the lanyard

to fire the round.

I do not remember the weight of the

105mm shells but in Europe we had 155mm artillery pieces which each

shell weighed about 95 pounds. They were more modern than what was

used in basic training but were similar in function and were pulled

by half-track power units. The range was in the vicinity of 3 miles

to 12 miles and therefore were not intended for direct fire combat.

The limited mobility and lack of armor protection placed the artillery

in more of a supporting role.

Basic training included getting a knowledge

of the equipment, practice in the operation but very limited use of

live ammunition. Our training in the use of the carbine allowed for

more actual firing on the range and I was proud to get an "Expert"

scoring. Other memorable duties included K-P, latrine duty, guard

duty and picking up cigarette butts. I remember a 3 day stretch of

K-P duty for getting in a half-hour late from a pass. The potato peeling,

pan washing, etc., was not so bad but I detested the requirement of

rewashing the windows or looking busy when there was nothing more

to do.

One of the things I especially enjoyed

about basic training was going to the P-X each evening and buying

a pint of ice cream. This was a tradition among several of my friends

and it was part of my body and health training.

An unpleasant memory in basic was the

witnessing of a senseless beating in a chow line outside the mess

hall. I have no idea what prompted it but someone talked back to a

bully type soldier, who thought he was king of the camp and he literally

beat him up with non one interfering. With my rural upbringing this

behavior bothered me greatly. I now realize this would not be unusual

today but at the time, even in an army camp, it was a rare occurrence.

In summary regarding my basic training

it was a positive experience and I feel the mission was accomplished.

I came out of it probably in the best physical condition of my life,

my hair was curly, I weighed about 180 pounds and I was proud to come

home to see Betty and my family.

Fort Mead, Maryland

All travel between camps in the States

was by train and in some cases the entire passenger car would be reserved

for military personnel.

My next assignment was to report to

Fort Mead, Maryland, where I spent 3 or 4 months. Part of the time

was devoted to infantry training and more to the unloading of bombs

and ammunition from railroad cars to be placed in ships for shipment

overseas. Another activity I remember was the repeated checking of

our clothes, gas mask, mess gear, blankets, duffel bag, etc., on the

open parade ground in preparation for shipment overseas. The only

reasoning I can see for this was an a drill for following orders and

not questioning assignments regardless of how unimportant these orders

might be. I do not think it would be an exaggeration to say we did

this 40 or 50 times in a two month period.

Off to England

On May 11, 1944 we boarded a troop ship

USS America with over 5000 on board and landed in England 10

days later. I was placed in a replacement camp with no information

regarding where or what type of unit I would be assigned to. Training

consisted of long marches, bayonet drills, and whatever could be done

without the benefit of artillery hardware. Air raid sirens frequently

sounded but no bombing or strafing ever occurred at the camp.

During the early morning hours and all

during D-Day June 6, 1944, American bombers and fighter planes filled

the sky leaving England and returning from Normandy. We knew the invasion

had taken place but reports were sketchy.

Photo postcard sent from

France

France, August 1944

Replacements were coming in and leaving

daily and it became a wait-wait exercise. After about 60 days of this

a notice came out asking for volunteers in the paratroop corps. A

friend of mine and I decided we would sign up which was strange considering

I had never been in a plane. Before anything could be acted on we

were ordered to move out and were loaded on a ship to cross the English

Channel and as we approached the coast of France we were lowered to

landing crafts and upon landing on Utah Beach were loaded on trucks

and taken to our individual companies.

I became a part of the 945th Field Artillery

Battalion in the Third Army but at what location I will never know.

For years after the war I felt critical about the army's lack of information

to the troops regarding location and missions. It was as though, be

where we want you to be, go where ordered and do what you are told

to do - no questions asked. Looking back there may have been some

of this but I realize now much of that was by necessity -- assembly

beyond your own individual squad was rare -- and I certainly could

have been more inquisitive and assertive in finding out this information.

It apparently was not that important to me at that time.

The Reality of War

Very soon after joining the 945th I

found out what war was all about and it has haunted me over the years.

I do not know if I can express it in a meaningful manner but the emotional

shock was followed more dramatically in the months that followed.

It was late afternoon in a partially

wooded area. Our battery of 155mm Howitzer (Rifle type) was arranged

in a semi-circle pattern. There were 155mm long Toms in a similiar

pattern about 1/4 miles behind us and the larger unit farther back

in the distance. The details are not important but we knew that we

were a part of a spearhead in progress.

At about dusk we were told there was

a mess truck in the wooded area where we could pick up C-rations and

K-rations along with something to drink. When I got within 100 feet

of the truck there were 3 dead Germans and after looking at them as

the enemy off to one side by a fence row were 3 dead Americans. The

futility and realism of war suddenly came over me which was topped

off, on my walk back to the fox hole I had started, by the body of

another German with his eyelids wide open. I was frightened and sad

that these killings had taken place only hours earlier.

During the night we would rotate our

guard duty and a common function of our artillery unit was the firing

of single rounds periodically called harassing fire missions.

One advantage of the artillery was that

we did not have to move as long as our target was within range so

we were often in one location for several days and if so we could

have a hot meal. Occasionally we would be pulled back for a few days

rest, regroup, and the best of all, mail-call. I was and always will

be thankful to Betty and my family for the letters they wrote. The

uncertainties of the war were hard on everyone and by this time, or

soon after, three of my cousins had already been killed.

It must have been shortly before Thanksgiving

we were told that General George Patton would be in the area. I remember

seeing him riding in an open jeep, on a road several hundred yards

from our artillery station, with his ivory handled pistols strapped

to his side. The visit was brief and uneventful.

The rains slowed down the movement and

I remember being thankful for overshoes on Thanksgiving Day. We did

not have sleeping bags but would fabricate one with wool blankets

and pup tent canvas and twine. Everyone was in the same boat and I

don't recall any serious complaining. If we were in one place long

enough we would receive copies of the Stars and Stripes.

The Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge took place from

December 16, 1944 through January 31, 1945. Our unit was located somewhere

near Metz when we got word of heavy losses in the area of Bastogne.

We were loaded in half-tracks when the

company commander told us replacements were needed in the Armored

infantry and he proceeded to read off names of all those being reassigned.

One of those called was seated next to me and he broke down crying.

I asked if it would be okay for me to take his place which was immediately

done. I often wondered what happened to him and he has probably wondered

the same about me. I knew nothing about him except that I thought

he was much younger.

Axel's writing on

the back of the picture: "Scheider & myself with a small

pup. June 11, 1945 Burgel Germany"

We were told we would receive a couple

weeks of infantry training but within three days were on the front

line with the 6th Armored Division, had switched our carbines for

M-1 rifles, hand grenades and had thrown away our gas masks. I remember

one of the three days in route was Christmas Day 1944 and we were

served a nice dinner at Metz.

Axel's writing on the back of the

picture: "Myself with trusty M1 and our squads track named

Christine by the driver from Missouri. Picture taken June 11,

1945. Pretty blurred but I'll send it anyway."

Another haunting memory that has stayed

with me includes visions of the destruction and loss of lives in the

Bastonge area. Strafing, mortar shelling, and tank battles were still

taking place but fortunately the main carnage was about over when

I got there. The memory I mentioned was seeing open rack trucks loaded

with frozen bodies piled like cord wood hauling them away and the

disgusting scene of seeing our own tanks going out of their way to

run over the bodies of Germans. I am sure there were many areas of

the war where masses of military equipment were destroyed but this

was the most I had witnessed.

The armored infantry troops moved either

by half-track armored personnel carriers or by walking. These troops

were generally accompanied by or preceded by tanks. I remember some

night moves in wooded areas that seemed to take all night. We held

on to the soldier's ammunition belt ahead of us and on some occasions

the line would be broken and it may be minutes or hours before the

line would be connected again to advance further. Naturally there

was no talking or verbal commands. Our stay in the Battle of the Bulge

was perhaps three weeks, the most frightening for me I believe was

outpost duty when alone and having to challenge or report any sightings.

Compared with the regular infantry we had the luxury of tank support

in almost all instances.

Our Division crossed the Roer river

on a pontoon bridge built by the Engineers Corps and several weeks

later crossed the Rhine a the city of Mainz after two days on the

west bank. After crossing the Rhine resistance was intermittent and

risk taking was high to make rapid advances. I saw tanks destroyed

by the German 88mm Panzers that air support or other strrategies may

have avoided. This is speculative as I did not know the big picture

but my sense was that miles advanced per day took on too much importance.

Off to Hospital

In April I became ill with acute hepatitis.

The airport at Frankfort was now under American control and they flew

me and many others by DC-3 to Hospital between Paris and Versailles.

My first plane ride was on a stretcher. My eyes and face had a yellow

cast and one of the the first things the doctor did was cut off my

high school class ring as I had an infection from a minor cut. He

inserted a flat rubber strip through the tip of my finger to act as

a drain. A day or so after I entered hospital the news came that Franklin

D. Roosevel had died and that was April 12, 1945.

Back to my Company

On the day the European war was over,

May 7, 1945 I was able to get a pass to go to Paris and within a short

time I started my trip back to my company. Travel was by train and

for much of the distance wooden box cars were used (called 40 and

8s, supposedly for 40 men or 8 horses during WWI). I was reminded

of those recently when seeing the movie "Schindler's List".

Some of the time we would take turns riding on top and for the final

leg of the trip we were picked up by trucks and routed to the various

units.

Paris snapshot, May 7

1945

A familiar face - My neighbor from

Cotesfield, Nebraska

A nice surprise was in store for me

just before being picked up by the company trucks to return to my

unit. While going through the chow line a familiar voice said "Hello

neighbor." It was Leonard Vlach who had been our neighbor on

the farm and he was the first and only familiar face I saw while in

the military. Leonard was the last person I would guess to end up

as a cook in the army. We met in the evening while he was baking pineapple

upside-down sheet cake and I stayed there two or three days which

was nice.

When I arrived back at the Sixth Armored

Division we were in a part of old Poland and it was there that I saw

the first Russian troops. Before going to hospital I had been acting

squad leader for several weeks and during my absence they had filled

that position with a corporal and awarded him a bronze star medal.

This was alittle disappointing to me as I would have liked to have

had the promotion.

During our stay at this location, we

were relatively close to one of the Death Camps and one day anyone

who wanted to visit could go. For some reason I declined and although

I often regretted not going, the decision not to go was probably for

the best.

Home to the U.S.

We soon made our way back to the coast

of France and after weeks of counting points and listening to rumors

of whether or not we would be sent to the Pacific, we were loaded

on a French Liberty Ship and were headed on a 14 day journey to the

United States. The bad part about the trip was that it was overloaded

with troops. You could hardly turn over because of the way the bunks

were stacked and the weather was bad resulting in sea sickness for

several days.

The good things about the trip were

that we were going home and the song being sung when we left the US

"Over there, Over there, You won't be back till it's over, over

there" could be erased. Also, there were quiet times when the

porpoises would follow the ship in formation with great sunsets; and

you can imagine the excitement when the announcement was made that

the atomic bomb and been dropped and a couple of days later that the

Japanese had surrendered. I can still remember the relief that the

was actually over.

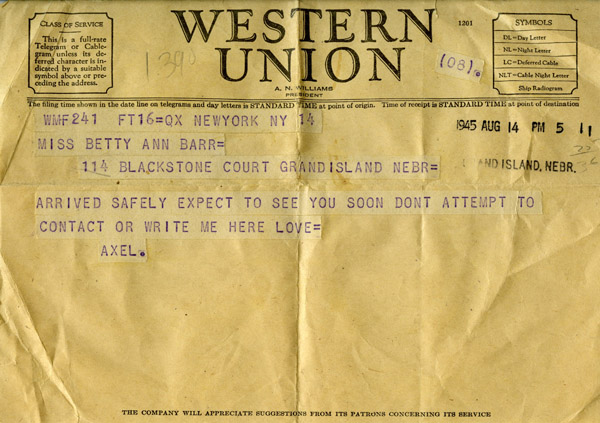

When we arrived in New York on August

14, 1945 and sailed past the Statue of Liberty, there was a band greeting

our return. Everyone possible was on the top deck and on the port

side of the ship causing it to list. The French Captain announced

over the loud speaker in broken English, "Please move to the

other side of the ship, it is extremely dangerous" and enough

people moved to reduce the tilting effect.

August 14, 1945

We were all given about 30 days leave

which was great. For the balance of my military time I was in a camp

in Texas guarding prisoners two hours on and four hours off round

the clock. This continued for about three months until my discharge

at Camp Fannin, Texas on December 20, 1945.

Army Discharge, December 20, 1945

My discharge lists my organization as

Co. C 9th Armored Infantry Bn. 6th Armored Division. Battles and campaigns

included the Ardennes, Rhineland, Central Europe GO33, WD45. Decorations

and citations include the Combat Infantryman Badge, American Theatre

Campaign Medal, EAME Campaign Medal with 3 bronze-stars, World War

II Victory Medal and Good Conduct Medal plus bronze star medals.

Taking the time to sit down and write

this has helped me put a number of things in perspective. Two and

half years out of a lifetime seems like an insignificant amount but

to many their military time has become the most important facet of

their lives.

Fortunately, it does not carry this

importance to me but it did teach me to value life more dearly, to

appreciate the comforts of a warm house and a good bed, and perhaps

even more the love of Betty and our family.

Reminiscing causes me to think again

of parents and the hours of worry and prayer they must have felt during

the war. I feel certain they knew this concern was appreciated but

it would have been nice to have told them so. As a parent now I can

only imagine how I would feel.

Before leaving Germany I had a large

Nazi flag that I had picked up going through homes near the Rhine

river. I sent it home and was told later that when my mother received

it she promptly burned it in the trash barrel in the back yard. I

never asked her about it and she never mentioned it but looking back

it was not a very considerate thing for me to send. Knowing my mother

there was no debate in her mind about what action to take.

Axel holding Leila and

Russell with niece Janice Boilesen on his shoulders at his parent's

Cotesfield farm

I could have been more descriptive in

elaborating on strafing, artillery and mortar attacks which were the

more serious threats on my life. Fortunately, I was never involved

in hand to hand combat. I was never in a position of having to be

a hero but am proud to have always followed orders.

The military has taken serious criticism

over the years and I may have been a party to some of this but when

I think of what our country built up to resist the Germans and Japanese

forces in World War II I am amazed. Just the logistics of these operations

in so many parts of the world and so far away form the U.S. is unbelievable

(and without a computer in every foxhole which some would believe

is necessary today).

Without sounding overly patriotic I

have to conclude that I am proud of my military service but will always

loathe the idea of war.

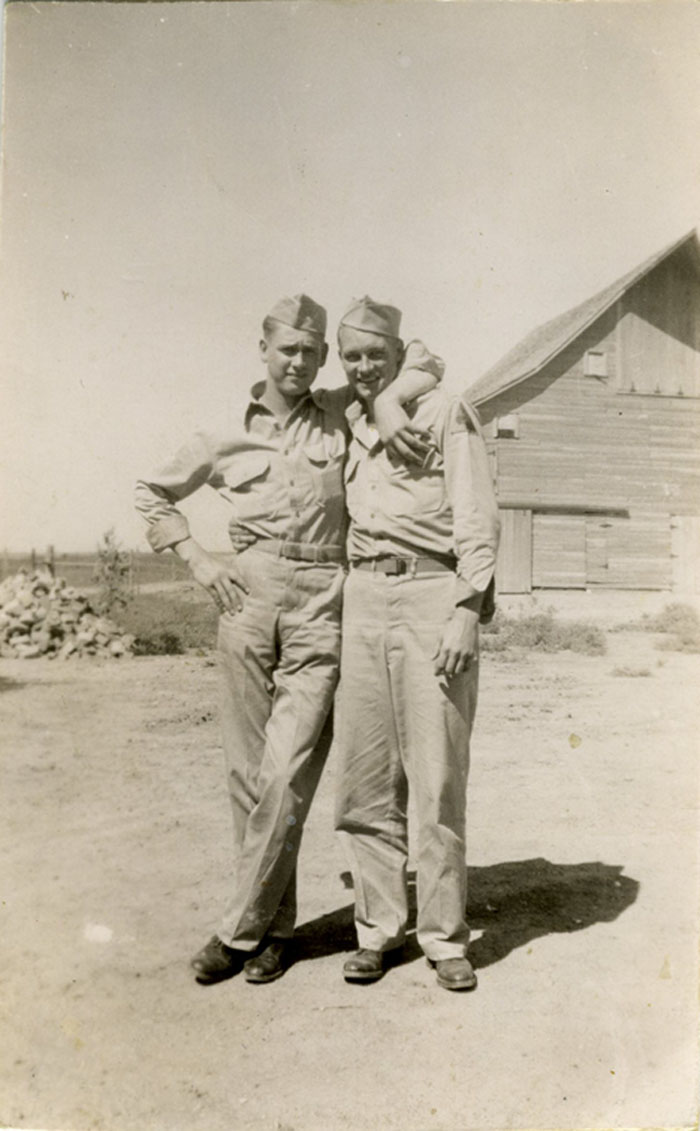

Axel's cousin Dwain R. Rasmussen on

left next to Axel while both were on leave in Cotesfield prior to

their deployments in Europe. Dwain's B-17 went down in the English

Channel on January 9, 1945. He was S/Sgt 385th Bombardment Group

551st Squad 8th Air Force England and flew over 25 missions. Dwain

was the son of Rasmus Jensen Rasmussen and Axelina Boilesen Rasmussen.

Dwain Rasmussen Draft

Card Registration - Dwain's number called up in October 1942

Axel Boilesen Draft Card

Registration

Axel's cousin Eudell R. Nielsen (b.

June 2, 1922) was killed in action in Italy on November 4, 1943. Pfc.

Nielsen was the son of Mr. and Mrs. Ray Nielsen. He went overseas

in March 1943 with Company F, 168th Infantry, 34th Division, and was

stationed in North Africa before going to Italy. Eudell's mother Josephine

A. Jensen Nielsen (b. Dannevirke, NE August 25, 1898) was the sister

of Axel's mother.

Howard County Herald,

December 8, 1943

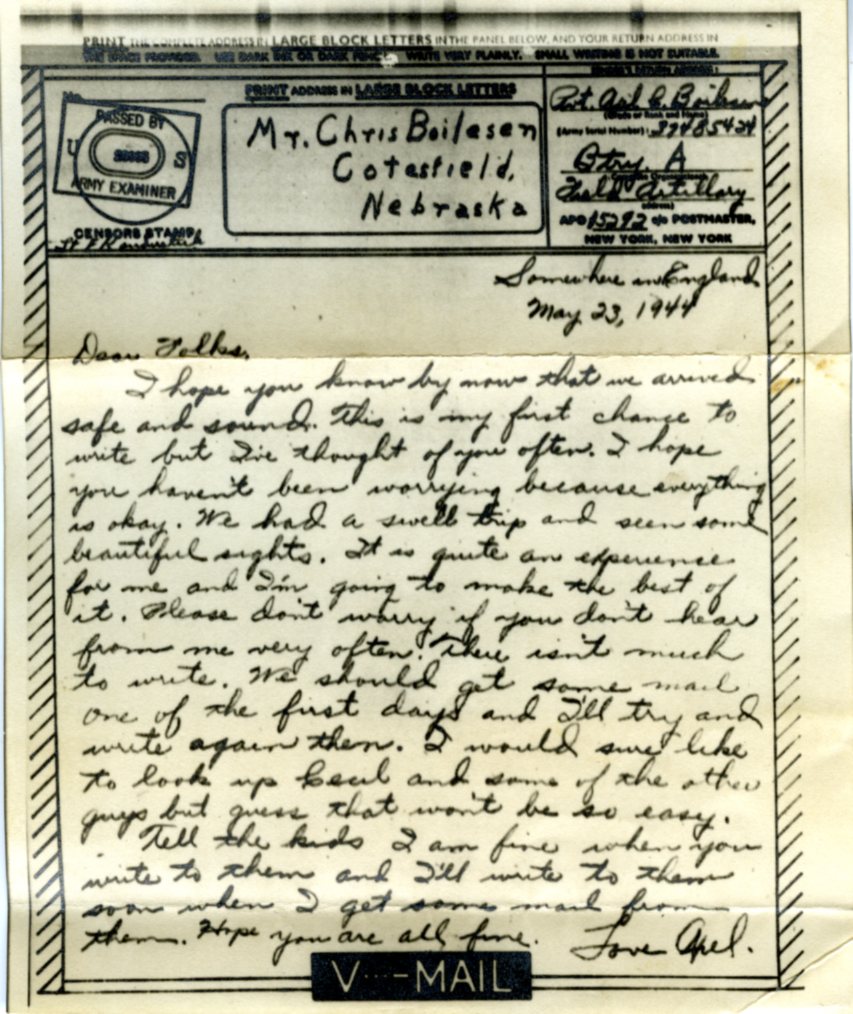

V-Mail sent to parents May 23, 1944

prior to joining the 945th Field Artillery Battalion of the Third

Army in France.

|